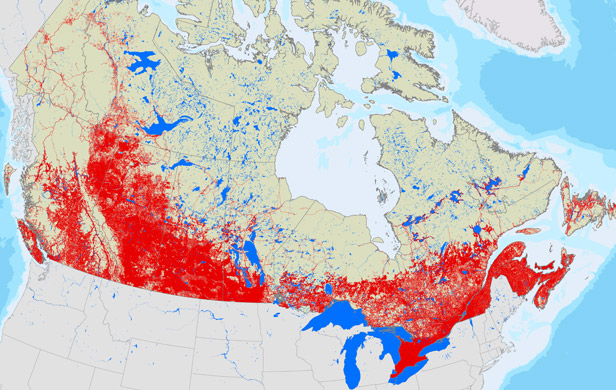

A national study suggests that Alberta has disturbed more natural landscape than any other province.

The analysis by Global Forest Watch adds that Wild Rose Country also has two of the three areas in Canada where the rate of disturbance is the highest.

“There were at least three major hotspots, two in Alberta,” said report author Peter Lee.

The report (download here) combines government data, satellite imagery and cropland maps to look at human intrusions in the last decade into all major Canadian ecozones. Those disruptions included everything from roads to seismic lines to clearcuts to croplands.

“We took all the available credible data sets that we could find and combined them all,” said Lee. “We ended up with what we believe is the best available map of human footprint across Canada.”

Alberta leads in the amount of land disturbed at about 410,000 square kilometres. Almost two-thirds of the province — 62 per cent — has seen industrial or agricultural intrusion.

Saskatchewan, at 46 per cent, is second among the larger provinces. Quebec comes nearest in area with 347,000 square kilometres.

The Maritime provinces actually have the highest rate of disturbance. The human footprint in Prince Edward Island, New Brunswick and Nova Scotia is 94, 85 and 72 per cent respectively of each province’s total area. But those provinces are so relatively small that the actual amount of disturbed land is dwarfed by totals elsewhere.

When Lee compared the current map to one developed about 10 years ago, he found two of three areas where the rate of development was highest were in Alberta as well — one was in the oilsands region; the other along the eastern slopes of the Rockies.

The third area is in a heavily logged part of northern Quebec. New intrusion in northeastern British Columbia, where there is extensive energy development, is almost as heavy.

Lee said development in the three top zones is pushing into previously untouched land at the rate of five to 10 kilometres a year.

The report’s calculations include a 500-metre buffer zone, which corresponds to the distance animals such as woodland caribou tend to keep between themselves and development.

Duncan MacDonnell of Alberta Environment said the government has plans to set aside about 20 per cent of the remaining boreal forest, which covers the northern third of the province.

That includes about 20,000 square kilometres in the oilsands region. MacDonnell said Alberta plans to eventually combine old and new protected areas to create the largest connected boreal conservation area in North America.

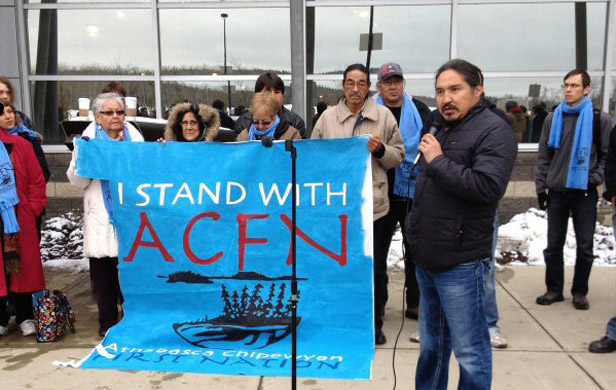

Those plans haven’t been implemented and all are the subject of controversy with area aboriginals.

MacDonnell said the province is developing land-use plans for the entire province which are intended to balance pressures on the landscape.

Representatives from the federal government were not available for comment.

Lee notes his findings come at a time when Canadian and provincial policies on development are being increasingly scrutinized, whether they involve forestry, energy or agriculture. He said this sort of basic, common-sense data-gathering should be done by Ottawa.

“It’s those sort of general questions that the person in the street asks,” said Lee. “Where are all the disturbances in Canada? Where are the pristine areas?

“This is a simple monitoring analysis that should be done and could very easily be done by the feds … (but) they’re not doing it.”