By Graeme Pole

Thoreau said, among other things, “…beware of all enterprises that require new clothes.” Aboard the BC Ferry Northern Adventure, departing Prince Rupert and bound for Haida Gwaii, I trained my camera on the southern tip of Digby Island, recording images through a liquid sky. Three months earlier, while our family had picked a route through hemlock, cedar, and beach logs on that island, we had encountered a team of “archaeologists,” meticulously scribbling notebook entries as they decorated ancient spirit trees with fluorescent yellow flagging tape. New clothes.

Confronted with a red cedar far too massive to encircle open-armed, and draped with yellow plastic, our youngest daughter asked me that day why the flagged trees were so special. Her question was genuinely innocent. My impromptu reply surprised me for being as inspired as it was brief: “Every tree is special.” I withheld elaborating. I could not bear to unload on our then seven-year old, half a lifetime’s cynicism derived from matters environmental.

The bearers of that flagging tape, who had helicoptered to work from Seal Cove that morning, and who would helicopter home that afternoon, needed to document every instance of culturally modified tree on south Digby Island. This, so that Aurora LNG could comply with a tedious impediment to business, known as an environmental assessment process, before intending to proceed, with the blessings of governments, to utterly destroy the place.

Legions of “biostitutes”

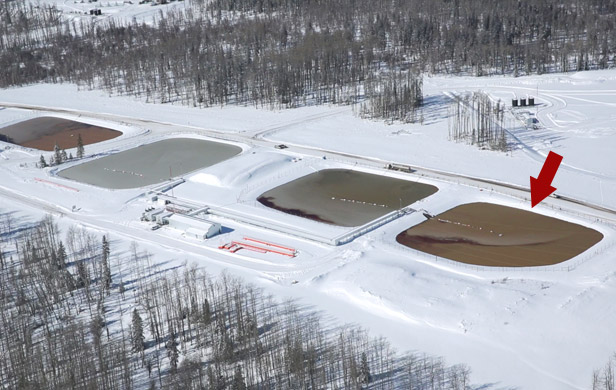

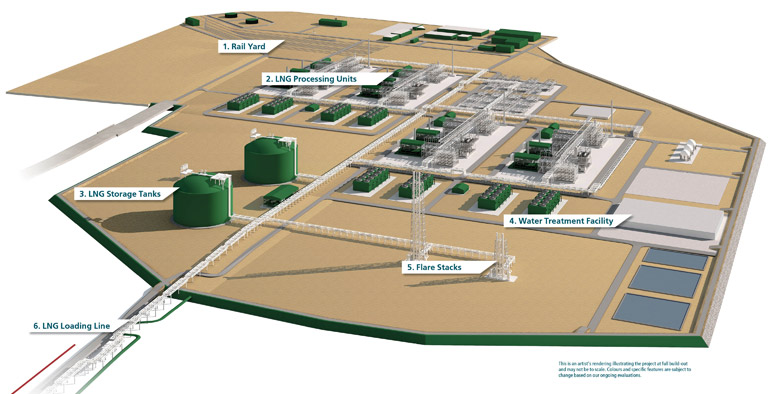

As the Northern Adventure chugged along, I attempted to visualize Aurora LNG’s conceptual plans (three of them) for berthing facilities among the islets off the southeastern tip of Digby Island. Those berths would accommodate ocean-going vessels 345 metres long – ships that would load and transport a dangerous cargo closer to human settlement (Dodge Cove, Metllakatla, and Prince Rupert) than the LNG industry itself deems safe. How can anyone in Prince Rupert get a good night’s sleep anymore?

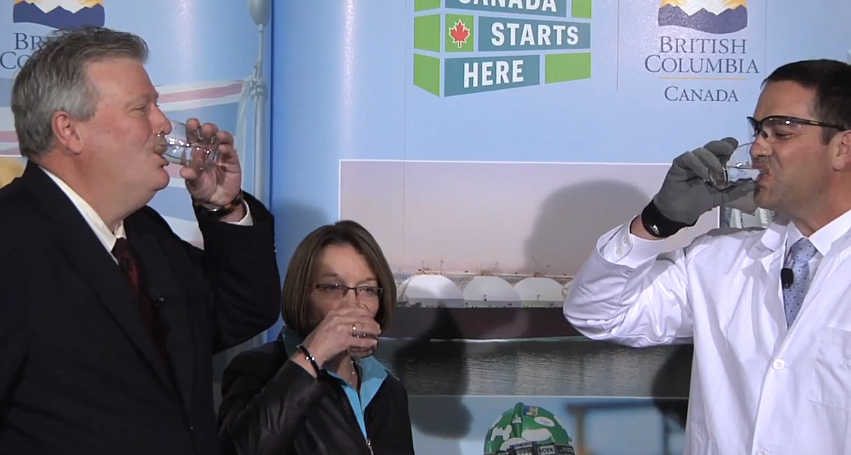

Some contractor on the company’s payroll had supposedly done the fieldwork; had checked the soundings and the substrate, had given a cursory nod to wild species and natural processes, had deep-sixed concerns over risks to human life and to the circulating atmosphere of the planet, and had nonetheless drafted the plans. How much money does it take, how much take-home pay, to utterly pervert a person’s connection to place, to fresh air, wild things, and clean water; to permit a person educated in environmental science to say: “This will work. Build it here. We can mitigate. We can get to ‘yes’.”

I now agree with a sentiment that I initially had found repulsive: These people, doubtless well-intentioned at the outset, and now with diplomas and degrees now in hand, have become biostitutes. And there are legions of them, ATV-ing and helicoptering their per-diemed ways across the wilds of BC.

A bald eagle wheeled by. I watched the wind pummel the bird as it turned a wing skyward and fought to hold its track.

North of Hazelton

As Digby Island fell away to stern, a woman interrupted my silent lament, joining me at the starboard railing where I sought shelter from the rain under one of the lifeboat davits. She asked where I was from. “North of Hazelton.” Brief rain-soaked silence. “Beautiful country,” she replied. “My son has been working there for two years with an environmental company. Finding the best place for the pipeline to go.”

When we made landfall at Skidegate, Premier Clark and Petronas were the top story on the CBC Radio news. The Petronas board of directors had given Pacific Northwest LNG conditional approval. TransCanada Pipelines was already saying that it would begin, within six months, construction of the fracked gas pipeline that would supply the LNG plant proposed for Lelu Island in the Skeena estuary and, perhaps inconsequentially, wreck the place some 300 kilometres upstream that my wife and I had chosen to make home, exactly sixteen years ago.

By late evening that day, newsfeeds were reporting that the BC Oil and Gas Commission had issued the first two construction permits for that pipeline.

No matter

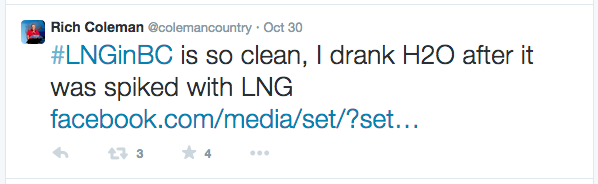

No matter that the federal environmental assessment of Pacific Northwest LNG – the destination of that proposed pipeline – was still underway, with the principal concern being impacts to wild salmon. No matter that Madii ‘Lii Camp of the Gitxsan First Nation nobly shuts down a 32 km length of the proposed pipeline’s route on unceded territory. No matter that this one LNG plant would increase the province’s greenhouse gas emissions by 8.5 percent over 2012 levels, at a time when law states that the province must decrease those emissions by 20 percent from 2007 levels. No matter that the “clean” label of LNG is a lie – the lifecycle emissions of shale gas converted to LNG are 43 percent dirtier than burning coal to achieve the same BTUs.

No matter that two of BC’s LNG proponents have atrocious environmental and human rights records elsewhere in the world. Sukanto Tanoto, president of Woodfibre LNG (proposed for Howe Sound), has been called “Indonesia’s lead driver of rainforest destruction.” In 2012 he was found guilty of US tax evasion and agreed to pay over $200 million in fines. Petronas has been accused of participating in “environmental genocide” in Sudan. (During her Asian LNG junkets, Premier Clark posed for photo ops with Tanoto and with Shamsul Abbas, then CEO of Petronas.)

No matter that the Blueberry River First Nations, in part seeking to thwart the upturn in fracking that the LNG industry would require, have filed suit in the Supreme Court of British Columbia over the breach of Treaty 8 that the oil and gas industry has brought to bear on their traditional lands. No matter. No matter. No matter. A chaos of vain carts before a stampede of proud horses.

“Generational opportunity”

For northwestern BC, Premier Clark’s ”generational opportunity” of an LNG industry requires of locals – who have a storied history with the comings and goings of boom and bust industries – an acceptance of more new clothes. A plague of white pick-up trucks descends on the landscape while helicopters buzz overhead at the edges of human settlement, sometimes at rooftop level. People who live elsewhere deem what will be imposed on the landscape of home, and why, and that it will be good for all. Motels and truck rental companies have a brief field day. Communities grapple with the ethics of huge money being proffered them by the agents of corporations from afar, who, until the dossier was dropped on their desk, had no idea where Hazelton was, or Gingolx, or Lax Kw’alaams.

Environmental consultants pop up in empty second floor suites all over Smithers, Terrace, Kitimat, and Prince Rupert, sometimes above the vacuous, street-level presence of their corporate employers. Smalltown main street becomes a meet-and-greet, “we are listening” playground for the denim and plaid, dressed-down suits of oil and gas corporations, domestic and foreign. And everyone knows that all these people want to do is to sell enough snake oil to allow the serpent to slither westward to the coast, to deliver its venom and devour a landscape, before it moves on to its next meal.

What money?

The provincial government claims that a billion dollars of taxable commerce has already taken place in BC’s new LNG economy. That’s a lot of leased trucks, hotel rooms, and restaurant meals. The revenue to the province (perhaps 70 million tax dollars) will not even begin to compensate for the government’s absolute giveaway of the methane resource. No net export taxes will be paid by LNG proponents until the capital costs of their projects have been recouped. The rate of levy then due the government will be less than you and I pay on a bag of potato chips.

Petronas and the government forecast the corporate investment in Pacific Northwest LNG, its pipeline, and its fracking fields at 36 Billion dollars. The government cannot estimate its own LNG expenses already incurred, but to anyone who has lent even a cursory ear to the media, to the parade of announced pay-offs to First Nations, and to the glut of government-sponsored open houses, it is evident that the sum already far exceeds 70 million dollars. It is well into the hundreds of millions of dollars, with pledges to First Nations of $1.6 billion more over the next 40 years.

If the experience of the LNG industry in Australia were to play out in BC, there could be project cost overruns that approach fifty percent. Thus it would be decades after the first LNG shovels were put in the ground before the taxpayers of BC might see a nickel of return. Yet governing politicians continue to utter lies about the economic benefits of the industry almost nightly on the news.

Fear, distrust and grief

Going broke and dealing with a poisoned land are potential long-term fallout of the proposed LNG economy. In the present, nothing of lasting value has been created by its supposed billion dollars of activity. To the contrary, much of lasting harm has come to pass. Fear, distrust and grief have been bred in the hearts and minds of those who live on the land and who love it the way that it is, along with a sense of betrayal that is profound.

How far will the people of northwestern BC bend before they break? How much crap are they willing to take from a governing party that they did not elect; from an industry that they did not ask to trespass in their home? How much longer can they live in a mythical land that is off-the-radar of those in other parts of the province, just enough of whom apparently thought that the BC Liberals were a good idea?

As I arrived in Queen Charlotte City and the radio news concluded, I could still feel the damp, the rain, and the wind of earlier that day, as Lelu Island had fallen to port. And I knew – damp or not – that the inherent condition of that intertidal realm would not be enough to prevent the ignition of northwestern BC in the coming social and environmental firestorm.

LNG as metaphor

From wellhead to waterline, and yes, even out to sea, LNG has become a metaphor for many things. Rendered to fundamentals, the proposed industry represents for BC and Canada a place of clear reckoning: Accept the industry, and nothing about how we care for the Earth will change at all, let alone for the better. Oppose the industry, and we buy time for the Earth, its people, and its wild species and natural processes while we (perhaps) collectively figure out less harmful ways and means to exist here.

Governments long ago, at the bidding of their corporate patrons, reached their sell-out decision points. Individuals from all walks are just now waking up to this. We will have to co-operate; will have to intend a different reality if a different reality is to come to pass.

Billions will drop at the slightest shaking from the money trees of industry and government. That’s nothing new. The takers, aboriginal and non-aboriginal, will take. Those opposed will fret and will hold their higher ground. The ocean will pulse twice daily on the shores of British Columbia, like a measuring heartbeat.

But beware. This will go on for but a while longer, until and if each of us takes on the new clothes that the Earth and the ticking times require.

Graeme Pole is a resident of the Kispiox Valley and the publisher of nomorepipelines.ca