Canada’s controversial mining sector may be the driving force behind the country’s insistence on protecting foreign investors’ rights over laws that guard its own citizens and environmental values. Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, like Stephen Harper before him, has doggedly defended corporate rights enshrined in an increasingly controversial aspect of many international trade deals, commonly referred to as an Investor-State Dispute Settlement (ISDS) clause. The provision protects foreign investors from domestic environmental and labour laws that could impede their development of a mine, a pipeline, or other potentially destructive industrial projects.

This is just one of the many fascinating revelations detailed by Canadian author Joyce Nelson in her new book Bypassing Dystopia: Hope-filled Challenges to Corporate Rule – the essential sequel to her 2016 book Beyond Banksters: Resisting the New Feudalism, which my late colleague Rafe Mair reviewed in these pages.

In her latest effort, available now from publisher Watershed Sentinel, Nelson paints a frightening picture of what The Economist has called “The Arbitration Game” – a system of corporate lawyers, hedge funds, industry-friendly governments and secretive international tribunals that enable corporations to profit off these clauses.

Canada defends Corporate Magna Carta

The idea grew out of a “magna carta for corporations”, which The World Bank endorsed in 1964, setting up the International Centre for the Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID) at its Washington, D.C. headquarters. There are four other venues for ISDS-related hearings, Nelson explains: the Permanent Court of Arbitration in the Hague, the Court of International Arbitration in London, the International Chamber of Commerce in Paris, and the Chamber of Commerce in Stockholm. These closed-door arbitration panels preside over cases arising from some 3,000 international investment agreements. “Lawsuits have been increasing exponentially in recent years, rising from about 15 per year in 2000, to 70 in 2015,” Nelson notes.

So important are these ISDS clauses to the Trudeau Government’s trade policy that when another government it’s negotiating with proposes to cut one from a draft agreement, it’s often a deal-breaker for Canada. “Reportedly, in 2016 Canadian officials stopped free trade talks with India ‘until it agreed to sign’ the Foreign Investment Promotion and Protection Agreement that included ISDS – which India still has not done,” Nelson writes, drawing on a story from The Council of Canadians. A source within the Canadian government’s NAFTA negotiation team told The Washington Examiner in 2017 that Canada “would refuse any changes to the existing [ISDS] system. ‘It would be something we couldn’t accept,’ the source said, adding that was ‘a pretty hard no.’”

The same issue threatened to topple the Canada-EU Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA) when the EU’s top court ruled in 2017 “that any deal allowing foreign investors to challenge national governments, such as the proposed investment court system within CETA, must be unanimously approved by all [28] EU states,” the Toronto Star’s Thomas Walkom explained. “Just a few weeks after EU’s top court ruling (May 2017), discussions around another Canada trade deal were ‘paused’ because of Trudeau’s insistence that it must include the ISDS provision,” Nelson adds.

Chapter 11 costs Canadian taxpayers

With all the pushback against ISDS clauses, why is the Trudeau Government so hell-bent on protecting foreign investors’ rights? After all, Canada is about as big a loser as they come from these international courts and related settlements. The country has been sued at least 39 times under NAFTA’s Chapter 11 ISDS clause, costing taxpayers over $300 million, though that figure is set to skyrocket this year, with big, new judgments in the pipeline. That’s all in addition to bizarre, voluntary settlements like the one Stephen Harper made with US forestry, pulp and paper company AbitibiBowater for $130 million in 2010.

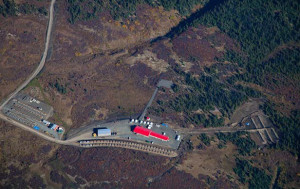

In that case, the provincial government of Newfoundland and Labrador had justifiably reclaimed water and electrical rights from the company after it closed the mill they were tied to, costing the community of Grand Falls-Windsor 800 jobs. The company sued for compensation over the expropriation of those rights and rather than try the case at the NAFTA tribunal, the federal Conservative government cut one of the largest Chapter 11-related cheques ever written at the time.

Today, that figure is less astonishing, compared to the ballooning settlements and judgements under ISDS clauses. Canada just lost its appeal of a $570 million judgement against it over US concrete company Bilcon’s rejected quarry in Nova Scotia. And the country could well face its biggest ISDS judgement yet if Texas-based Kinder Morgan decides to file a Chapter 11 case over the Trans Mountain Pipeline.

Digging for gold through ISDS claims

So, on the surface, Canadian leaders’ support for these clauses is puzzling. But Nelson offers a compelling explanation for why Trudeau and company would continue to champion investors’ rights, writing:

[quote]A February 2017 report from Corporate Europe Observatory (CEO) called Gold-Digging with Investor-State Lawsuits sheds some further light on the situation. It states that Canadian mining corporations are “among the worst in the world when it comes to using investor-state lawsuits to bully governments” into backtracking on environmental regulations: “62% of the 55 ISDS cases that involved a Canadian investor until 2015 were in the resource or energy sectors. And 58% of the cases challenged resource management or environmental protection measures.”[/quote]

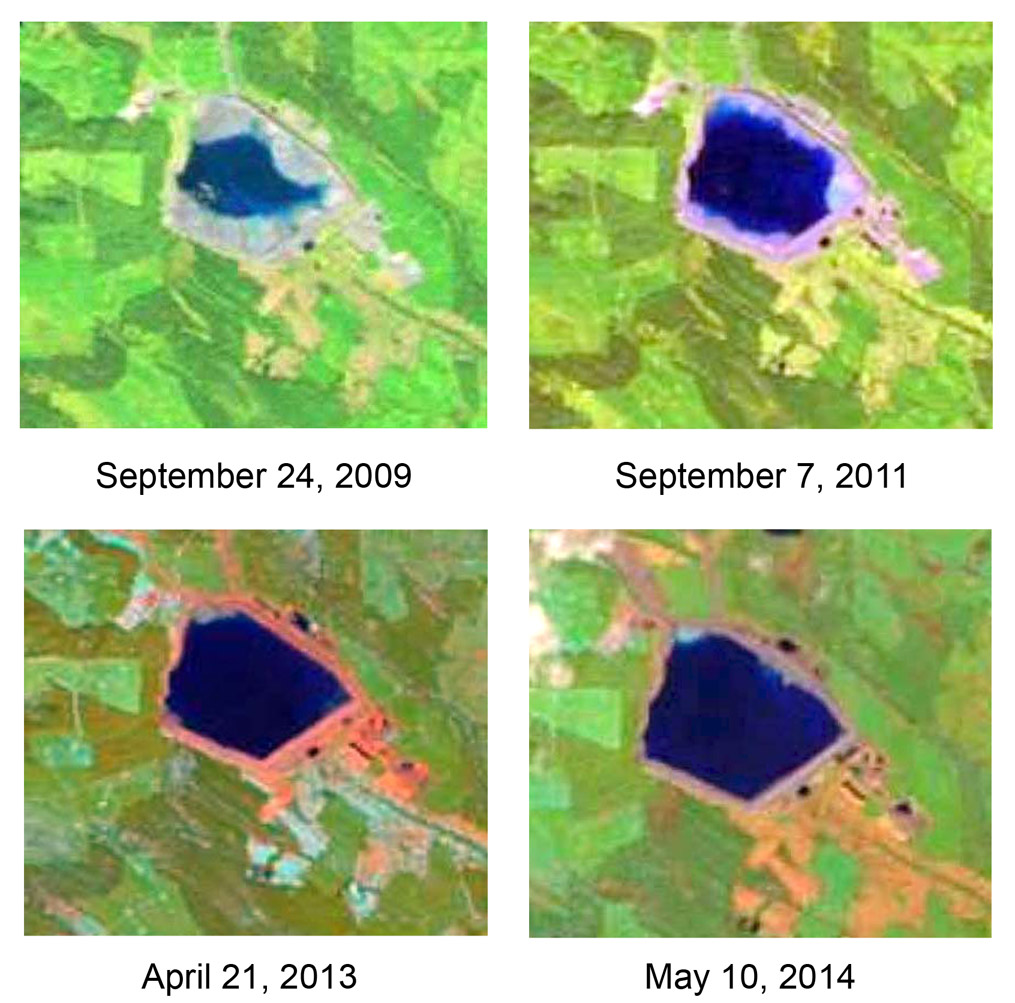

Nelson underscores this point with the dispute between two Canadian mining companies and El Salvador. “For more than a decade, the people of El Salvador fought against a mining site proposed by Canadian gold mining company Pacific Rim,” she writes. “Understandably, they were concerned that toxic cyanide from the mining would enter the watershed of the Rio Lempa, a river that provides water to more than half of El Salvador’s population.”

But when Pacific Rim was acquired by larger Canadian-Australian mining company OceanaGold in 2013, the new owner, despite holding only a preliminary exploration licence, launched a $300 million ISDS challenge against El Salvador for balking at the project’s environmental impact statement. The tiny nation eventually won the case, but still had to foot a $12 million legal bill for its defence. (Despite a 2016 court order to reimburse the country for $8 million of these costs, OceanaGold had yet to pay up by the time the 120-day deadline passed in early 2017).

Hedge funds join the “arbitration game”

The ISDS “arbitration game” could prove highly lucrative for Canadian mining firm Gabriel Resources through its $4.4 billion claim against Romania, over the government’s rejection of permits for the company’s proposed Rosia Montana mine. Corporate Europe Observatory’s 2017 report documents the case, raising a troubling new development in the world of investor rights litigation – the money hedge funds are putting up to back and profit from such arbitration:

[quote]Despite the secrecy, it has emerged that Gabriel’s claim is financially backed by Wall Street hedge fund Tenor Capital Management. Tenor pays Gabriel’s lawyers in exchange for getting a share of the compensation that the company might win. The [hedge] fund has already profited handsomely from an ISDS case of another Canadian mining company, Crystallex: it will cash in 35% of a whopping US$1.4 billion ruling against Venezuela from 2016 – a return of over 1,000% on the US $36 million that Tenor had initially injected in the claim. Such funding arrangements allow companies like Gabriel to draw out legal fights, driving up defence costs for states and [increasing] the likelihood that governments give in to corporate demands.[/quote]

Other companies and countries are getting into the game as well. Another major “investor” in ISDS litigation is New York-based Burford Capital, which describes itself plainly as “the world’s largest provider of arbitration and litigation finance.” The company reportedly made $140 million when an arbitration panel awarded its client $324 million from the government of Argentina over the country’s nationalization of the airline Aerolíneas Argentinas.

Meanwhile, Canada has become a major player in the global arbitration game. According to one of Nelson’s sources, Cecilia Olivet of the Netherlands-based Transnational Institute, Canada ranks fifth in the world in ISDS-related suits, led by its mining sector. “More than 60% of the world’s mining companies are headquartered in Canada (about 1,700 companies), operating more than 8,000 mining sites in over 100 countries,” Nelson adds.

“If these companies ‘are among the worst in the world’ when it comes to using ISDS lawsuits to bully governments, it becomes clearer why the Justin Trudeau government (and previous Canadian administrations) have been so adamant about trade deals needing to contain ISDS.”

Is the jig up for investor rights clauses?

Montreal-based writer and activist Yves Engler supports this notion, writing last year, “Nearly two years into their mandate the Trudeau regime has yet to follow through on any of their promises to rein in Canada’s controversial international mining sector. In fact, the Liberals have largely continued Harper’s aggressive support for mining companies.”

That should come as no surprise given the amount of lobbying access the industry has received from the Trudeau government. Between November of 2015, when Trudeau was sworn in, and March of 2018 (the last month for which data is available), federal government representatives recorded 636 communications (meetings, emails and phone calls) with The Mining Association of Canada, the industry’s chief lobby – according to data from Canada’s lobbying registry. That doesn’t include other groups and corporations within the sector.

Yet while Canada continues to push hard for ISDS clauses protecting its mining sector, many other countries are growing fed up with the arbitration game. As Nelson writes, “India – like Ecuador, South Africa, Bolivia, Venezuela, Indonesia, China and other countries resisting ISDS – has developed its own Model [Bilateral Investment Treaty] that requires investors to pursue disputes in public domestic courts for at least five years before moving on to international arbitration.”

If this trend continues, the Trudeau government will face increasingly hard choices between growing international trade and protecting its mining sector. Even Donald Trump reportedly wants to scrap Chapter 11, as Canada and the US renegotiate NAFTA. Trudeau would be wise to let him have his way on this one, rather than defending a clause that runs so contrary to regular Canadians’ interests.

The ISDS racket is just one of many important topics Nelson addresses in Bypassing Dystopia. The book serves two important functions – first, decoding the corporate jargon used to disguise what is really the transfer of wealth from the pockets of everyday citizens to the hidden offshore accounts of multinational corporations and the elite investor class. Terms like “quantitative easing” (bailouts for big banks), “austerity“ (passing the cost onto regular people), and ”asset recycling” (privatizing public assets) are translated into plain English, so the public can know what it’s up against.

The ISDS racket is just one of many important topics Nelson addresses in Bypassing Dystopia. The book serves two important functions – first, decoding the corporate jargon used to disguise what is really the transfer of wealth from the pockets of everyday citizens to the hidden offshore accounts of multinational corporations and the elite investor class. Terms like “quantitative easing” (bailouts for big banks), “austerity“ (passing the cost onto regular people), and ”asset recycling” (privatizing public assets) are translated into plain English, so the public can know what it’s up against.

The other role the book plays is offering solutions from empowering stories of resistance to these neoliberal economic policies. Through Rafael Correa’s Ecuador, Mexico’s Zappatistas, Spain’s “Indignados”, Cuba’s revolutionary organic farmers, the North American divestment movement, Denmark’s happiness-boosting social services, and Japan’s erasure of “sovereign debt” with smart central banking, Nelson provides a roadmap to liberation from the greedy banksters’ deathgrip on our environment and societies.

For all that, you need only buy her book.