by Bob Weber, The Canadian Press

EDMONTON – Opposition politicians are raising concerns over a report done for Alberta’s energy regulator that suggests doctors are reluctant to draw links between health problems and the energy industry.

“We do have a culture in this province which actively diminishes healthy and important debate about the health and environmental effects of our dominant industry,” NDP critic Rachel Notley said Monday.

David Swann, a Liberal member of the legislature, said the government doesn’t even want to know the truth. Said Swann, who lost his job as a public health doctor for speaking out on climate change during the Tory government of Ralph Klein:

[quote]It’s clear the government doesn’t really want to know the best science in some of these areas. They haven’t funded it, and they haven’t disseminated the knowledge appropriately to the physician population.[/quote]

Hearing begins into health effects from oilpatch operations

On Tuesday, a hearing is set to begin in Peace River, Alta., about the source and effects of odours that landowners blame on the local oilpatch, particularly the operations of Baytex Energy.

Baytex uses an unusual method of heating bitumen in above-ground tanks to extract the oil. Residents say the fumes from those heated tanks are causing powerful gassy smells and leading to symptoms that include severe headaches, dizziness, sinus congestion, muscle spasms, popping ears, memory loss, numbness, constipation, diarrhea, vomiting, eye twitching and fatigue.

Labs refuse to study health effects of petrochemical exposures

Among the reports commissioned for the hearing by the Alberta Energy Regulator is one from Margaret Sears, a doctor in chemical engineering, who has testified on environmental contamination for many bodies including the Royal Society of Canada.

Sears wrote that even though most health professionals believe petrochemical emissions affect health, Peace River doctors seemed unwilling to consider if the conditions their patients complained of were caused by long-term exposure to petrochemicals.

“There were reports from various sources that physicians would not diagnose a relationship between bitumen exposures and chronic symptoms, that physician care was refused for individuals suggesting such a connection,” she wrote.

Even medical labs refused to conduct an analysis when told it was to be used to try to establish such a link, said Sears.

Doctor refers patient to lawyer instead of offering treatment

One doctor, in a medical report released as part of the hearing, advised his patient “to go through environmental lawyers” and did not prescribe treatment.

Sears confirmed to The Canadian Press that her conclusions were based on interviews with both patients and doctors.

She wrote that the physicians’ reluctance stemmed in part from a lack of research they could use to form a credible opinion and in part from “fear of consequences.”

Conor not surprised

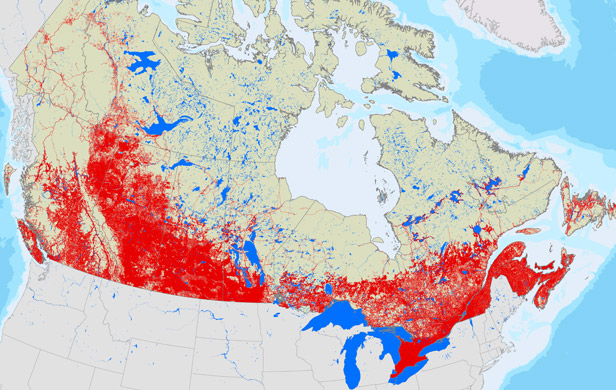

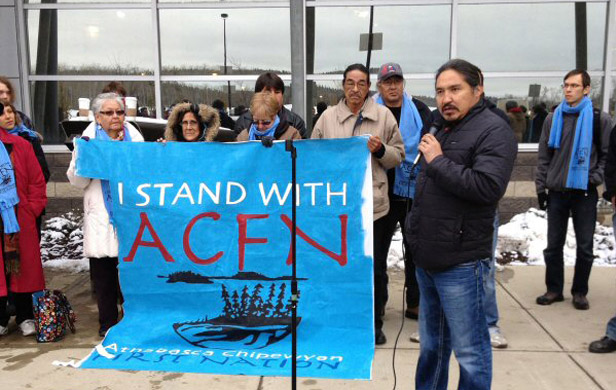

“I’m not surprised,” said Dr. John O’Connor, a doctor who was disciplined in 2007 for raising cancer concerns in the oilpatch community of Fort Chipewyan. The Alberta Cancer Board has since found elevated levels of four different cancers in the community.

“It has been said to me many a time over the last few years, or words to that effect,” he said.

[quote]It’s not easy. You set yourself up as a moving target.

[/quote]

Allan Garbutt, president of the Alberta Medical Association, said he couldn’t comment on the specific concerns in Sears’ report.

“I certainly agree that physicians must not feel intimidated in exercising their advocacy role,” he said.

“There would also be merit in exploring the report’s suggestion that better research on the impact of oil and gas emissions on patients and communities is needed for strong policy development. Better information, training and support for physicians to help diagnose their patients would always be welcome.”

Health Ministry downplays concerns

Matthew Grant, spokesman for Alberta Health Minister Fred Horne, downplayed Sears’s suggestions.

“No concerns of this nature have been forwarded to our office. We would always expect physicians to inform the government of any public health concerns they may have.”

Notley said the province has consistently avoided conducting research that could answer the kind of questions being raised in Peace River.

“The status quo is to believe that nothing’s wrong and all industry has to do is say, ‘Show us a mountain of evidence,'” she said. “It’s very imbalanced, and that imbalance works against people without the resources to build those mountains of evidence.”

Swann said Alberta public health doctors aren’t trained enough to be able to diagnose health complaints caused by environmental contamination.

“We haven’t been trained to do the physical assessment, order the right blood tests and put together the exposure with the health systems,” he said. “We’re working in ignorance, and there is the fear of challenging both government and industry in such a dominant industry activity here.”

Swann said his experience was widely noted among his colleagues.

“I paid a price, 10 years ago. I think the lesson most physicians took from that is that you speak up at your risk.”