Every baby is a biological miracle. In its development from conception to birth it undergoes a remarkable process summarized by “ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny” — a fetus growing into a human being moves through the entire succession of animal phyla, from the most simple unicellular organism to the most complicated of the multicellular. This process not only confirms the evolutionary history of life but highlights the incredible memory and genetic intelligence contained within a single fertilized cell.

Concurrent with this development of the fetus is the utter wonder of becoming sentient, of ascending through levels of consciousness until awareness is even aware of itself. “When you think about life, there’s nothing quite like it,” noted the philosopher, theologian and writer, Ron Atkinson. People who are only remotely aware of the implications of this notion are justifiably awestruck by everything that is alive — but, also, by the question of how everything came to be alive.

Genetically programmed to reproduce

In case anyone should forget about the importance of this question, however, biology looks after any lapses in memory. We are genetically programmed to be reproductive organisms, constantly being reminded of this by nature’s ingenuity. The mutual attraction of male and female is guaranteed by multiple mechanisms that range from subliminal pheromones and alluring odours to conspicuous shapes and subtle movements.

The pleasure of sex is just one obvious enticement to mate and reproduce. Most of our social structures, domestic traditions, dress habits, entertainment pastimes, eating rituals, philosophical notions and even religious precepts are strongly influenced or directly driven by sexuality and the biological imperative to regenerate the species. The urge to merge is so powerful that in some moments of reflection we must wonder whether our lives are served by sex, or sex is served by our lives.

The population explosion

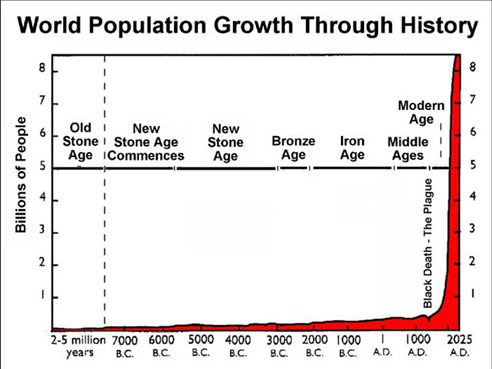

This question is best answered by numbers. For hundreds of millennia we were a few million scattered beings dispersed sparingly around the world’s continents. By the 16th century our entire human population was only 450 million. We have just recently become a species of billions. After centuries of incremental growth, our population reached 1 billion in 1804, then 2 billion in 1927, 3 billion in 1960, 4 billion in 1974, 5 billion in 1987, 6 billion in 1999 and 7 billion in 2011. It reached 7.3 billion in the early months of 2014, and is expected to be at 8.1 billion in 2025, 9.6 billion in 2050 and perhaps 10.9 billion in 2100.

Of course, the accuracy of these projected numbers is subject to many variables, including human-inflicted ecological disaster. But the proliferation of billions upon billions of people presents sobering uncertainties for the future of each additional baby. What will be the quality of life it inherits in a world of diminishing space and resources?

Biological miracle or ecological problem?

Each baby, despite being a biological miracle, is now part of a biological problem. What we have been doing naturally has now become unnatural — the reproductive success that our biology has always been attempting was never allowed by previous circumstances.

The constraints of fatal disease, food shortage, extreme climate and geographical isolation that once limited our numbers have mostly been removed by modern civilization. Indeed, population increases are a direct measure of the success of our organized institutions and technologies. The brutish cruelty of our long history is increasingly being replaced by abundance, comfort, health and longevity — in Sir Kenneth Clark’s personal view of Western history, Civilisation, he notes that one of greatest achievements of the 19th century was humanitarianism with all the variants of kindness that come with it. We have revolutionized the quality of our lives but the primordial biological urge continues unabated.

Population flatlining in affluent countries

In many affluent countries, sex has become more recreational than procreational. In these circumstances, the making of babies tends to be deliberate rather than inadvertent. The maternalistic and paternalistic drives of biology’s insistence may be as persuasive as ever but nature’s reproductive intentions can be controlled. Consequently, in many affluent cultures, the upward population curve is flattening, while in some countries it is falling — a 2012 United Nations study expects a population decline in 43 countries by 2050, a demographic skew that is already creating a different kind of demographic challenge.

Educating women the key in developing nations

This means that most of the projected population increases for 2050 and 2100 will be occurring in cultures that can least afford it. These are the places where biology’s harsh methods of trimming the excessive number of a species collide with humanity’s evolving sense of kindness. The humanitarian solution to too many people making too many babies is to encourage gender equality, to educate women, and to raise living standards — each reduces reproduction and population growth.

The reality of limits

The principal obstacle to raising living standards for large numbers of even more people is the reality of limits. The consumption that can be supported by a finite planet has already been exceeded by the existing affluent cultures. They are already using more resources than can be replaced by the biosphere. Any increase in the material well-being of significantly more people would raise the level of exploitation even further beyond sustainability.

The sobering conclusion is that the most humane solution to the population problem would probably create a catastrophic environmental one. Humanity has reproduced itself into a situation where the choices are either intolerable or untenable.

What to do?

What to do? No one really knows. It’s another of the unfolding dilemmas invented by our remarkable cleverness and inadequate foresight. As always, the individual choices we make and the specific things we do all combine to create a tide of consequences for which no one in particular is responsible, yet everyone in general is culpable. And now the biological urge to reproduce is in collision with the ecological warning to refrain.

At least, that’s what we would like to believe — that we can choose. But biology may be more powerful than thoughts, more insistent than restraint, more demanding than control. Reproduction is in our genes. It’s the principal driving mechanism of life, and we are unlikely to be exempt. This is confirmed by the miracle of each and every baby.

I have no idea what most of this article said. I had to stop reading after seeing Haeckel’s law spewed as though it were actually true. Stick to your realm of expertise or risk having all your ideas discredited.

The article seems pretty straight forward to me.

Exploding population vs finite resourses = Disaster.

Did you miss something?

When a species populates excessively nature finds a way to put the brakes on further expansion! Perhaps disease, food sources have declined and one of my favourites is the Prey find a way to limit the Predatory behaviour. Who are the predators, the 1%, for them growth is a must.

A free fire will not burn out until its fuel source is gone or its out of oxygen. My metaphor for greed.

Most people do not spend their lives in addiction, why, because it is not a place most people want to go, for good reason. Many people have a survival instinct that will prevail.

Or is the author suggesting people do not have a will of their own?