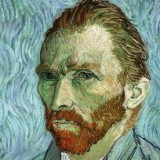

Almost everyone knows about the Dutch painter, Vincent van Gogh, and his turbulent life of abject poverty, bouts of insanity, total failure as an artist — he sold one painting in his career — and his eventual death from an apparently self-inflicted gunshot to his stomach.

This personal tragedy juxtaposes with his current popularity and success — one of his paintings, Portrait of Dr. Gachet, recently sold for an astounding $82.5 million. But van Gogh’s significance is not usually considered in a wider cultural context. This is what the art historian Modris Eksteins explores in his two books, Rites of Spring and Solar Dance: Genius, Forgery and the Crisis of Truth in the Modern Age (Maclean’s, Feb. 27/12).

To understand van Gogh’s deeper significance, we need to recognize that history is only meaningful in the grand sweeps that are rarely noticeable to those living at any given moment. So the details of ordinary life usually provide little perspective of what is actually happening until these daily events fall into the context of larger time frames. This explains why artists and historians are so important. And the two come together in Eksteins’ consideration of van Gogh.

Van Gogh’s present popularity, Eksteins argues, arises from the match of his personality with our present age — “an icon of authenticity for the age of doubt”. Van Gogh certainly didn’t seem to belong in his own time. During the span of his life, from 1853 to 1890, he embodied all the traits that were uncharacteristically Victorian. Instead of diverting the raw drives of life into duty, order and propriety, van Gogh lived them directly, like a unfettered animal following the creative urges of his instincts. He seemed to be wholly out of tune with the outward pulse of his era. But, as Eksteins argues, van Gogh was wholly in tune with the unconscious forces that were frustrating Victorian Europe at the end of the 19th century.

Europe was struggling with a “crisis of authenticity”, a pseudo certainty that felt hollow and hypocritical. In essence, van Gogh was living the life that many Victorians secretly desired but rarely fulfilled. It took the Great War and its aftermath to bring this obscure Dutch painter to prominence.

At the end of van Gogh’s life in 1890, Europe did not know it was careening toward catastrophe. But all the conditions were being set for the 1914 calamity of the First World War. As difficult as it is to believe today, most Europeans welcomed the conflict, enticed by the prospect of authentic experience and an opportunity to live all their high Victorian values of pride, loyalty and honour. They learned a sorry lesson. At the end of the destruction and carnage — at least nine million dead — Europe sat amid wreckage, a continent devastated physically, economically, socially, psychologically and philosophically.

Europe, in effect, had lived Vincent van Gogh’s life and could now identify with him in a way that was never possible during its previous innocence. Van Gogh’s popularity soared. He became an icon of the new century’s turmoil and intensity. In Eksteins’ words, “We choose our heroes out of our deepest concerns.” Or, expressed differently, the people we make into our heroes embody a part of ourselves that we do not always recognize at a conscious level. Thus our heroes creep into prominence, slithering sideways in curious disguises until we eventually understand how they define who we really are.

This brings us to the present, to the way history always repeats itself — the unfolding circumstances are always different enough to surprise us yet always similar enough to be familiar — and explains why van Gogh still looms so large in our imaginations. The First World War bred a half-century of tumult and shattered ideals, wreckage that we are still trying to reconcile with an image of better selves. Like the Victorians, we also live in a world of illusions.

We, in the 21st century, are not that different from the Victorians at the end of the 19th century on the brink of conflagration. Instead of their hollow decorum, propriety and duty, we are a culture of materialists and consumers, technological and scientific wizards wholly engrossed in our own biases. Just as the Victorians, we possess the same smug and compulsive indifference to the warning sirens screaming around us. The momentum of our cultural habits carries on with the same willful blindness that characterizes every civilization marching into its future — smart enough to observe what is happening but not quite able to measure its actual significance.

The brooding presence haunting us today, of course, is global environmental deterioration exacerbated by too many people consuming too much on a planet that is now too small, a destructive compulsion coupled with a momentum of greed that sometimes seems unstoppable. Our frenzy of resource extraction, energy consumption and industrial production makes the Victorians’ storied enthusiasm seem comatose.

Is our situation analogous to the Victorians? Will we re-live their naivety with an Armageddon of our own? The real answer is that we don’t know — yet. But rising numbers of ecologists, climatologists, biologists, economists, philosophers and almost everyone of intellectual and scientific substance are warning us of imminent and irreversible consequences that should give us pause for a very serious evaluation of our collective values and behaviour.

But maybe we already know. Perhaps this is why we are so drawn to Vincent van Gogh, the earthy, intense and self-destructive painter who risked all and lost all in the fire of his creative energy. Perhaps Eksteins’ insight — that “we choose our heroes out of our deepest concerns” — is truer than we realize.

I have not read the books, but the article raises interesting questions. Heroes, shadows, tricksters are not the stuff of erudite fancies; they are at work in our daily lives, confirm our cultural values, and even shape the future. First Nations people – among others – would attest to that in the longest historical terms and with far less rigid distinction between conscious and subconscious realms as typically formulated in modern Western societies.

Thus I cannot help but wonder if the growing interest in Van Gogh’s life and work throughout the twentieth century is for many rooted in an urbane, Euro-American fascination with personal development, psychotherapy and emotional liberation, and thus a type of narcissistic

projection which serves to appropriate the artist’s genius, compensate egos, mitigate suffering – real or imagined, and unwittingly perpetuate myths of the modernist world rather than open our eyes, minds and hearts.

On a separate note, and regarding BC and the Pacific Northwest in general, the article raised for me the specter of Emily Carr, whose life and work should have much to say about forces still at play in the bioregion. Do they? Just food for thought.

That is technical . not insightful.

Vincent would have remained unrecognized if it had not been for the work of his sister-in-law. Theo, Vincent’s brother, also died young but his wife Johanna van Gogh-Bonger dedicated her life to marketing Vincent, editing his letters to Theo (Theo’s letters to Vincent, of course, did not survive) and judiciously creating interest in his paintings – which was all she had. The publication of the letters in 1914 was what started the process.