Sometimes the magnitude of the environmental challenges facing us today seems overwhelming. So we traditionally examine the larger problem in fragmented details. We isolate one part of a huge complexity of issues and consider, for example, the decline in wild salmon populations, the dilemma of disposing of municipal garbage, the merits of banning cosmetic pesticides, the mechanics of efficient recycling, the task of building efficient cars, the best way of managing forests, the logistics of protecting our surroundings in parks, conservancies and agricultural land. These days, the list could go on and on. And each detail alone seems extremely complicated for anyone who has tried to solve any one of them.

But overshadowing every detailed environmental problem is a question that we dare not ask. What if industrialization itself, the very foundation of our material, economic and social existence, is not sustainable? What if we made a strategic mistake 250 years ago when we left a biologically based energy system and cultivated one based on fossil fuels – when we shifted from muscle power to machine power? The Industrial Revolution was literally revolutionary, exploding our capacity to produce, consume, and impact our environment. But what if this system, so beneficial to us and so ecologically disruptive, is not compatible with the natural laws and limits that we must respect if we are to live sustainably on our planet?

Such a question seems heretical given the incredible material wealth, comfort and technological ingenuity that industrialization has provided. Indeed, we can’t imagine our present world without such a high-powered system of production and distribution. Oil magnifies our human effort by a factor of 25,000 – one barrel contains the energy equivalent of 12 men labouring for one year. Fossil fuels account for most of our electricity and transportation, half our fertilizers, and all the incredible petro chemical products that amaze us – from plastics and tires to clothing and paint. Industrialization has so magnified human influence and control that it has enabled our population to burgeon from 700 million in 1750 to an astounding seven billion today.

But, has industrialization’s success been its failure? Is it the instrument that we are using to wreck our planet? Does it have key failings that make it fundamentally destructive and unsustainable? Thoughtful people are now asking this question. Derrick Jensen raises this issue in You Choose, an intense selection from a book of collected essays, Moral Ground. “Destroying the world is what this culture does. It’s what it has done from the beginning,” he writes. Our impact was once insignificantly small; it is now large enough to be causing structural and global ecological distress.

The failing, of course, is not with industrialization per se. It was not one of nature’s inventions, a quirk of evolution that suddenly found a new and novel adaptation. Like writing, money, morality and time, industrialization is our invention, our way of giving shape to the order, character, materials and surroundings we prefer. Because industrialization is an extension of ourselves, we use it as an instrument to design the world that we want. And herein, perhaps, lies the failing of industrialization – it amplifies our own failings.

Although we call ourselves homo sapiens, wise humans, we still have some learning to do. Our entire history as a species has been a wresting of survival from a natural world of adversities. Our habit has been combating our surroundings and competing with each other. We have, of course, cooperated with plants, animals and other people when this strategy has been advantageous to us. And we have profited considerably from this tactic.

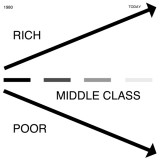

But cooperation has not been industrialization’s strategy. It has mostly been a process of taking, making and using what we want with little regard for environmental consequences. And, when we have coupled industrialization with such an extreme variant as free-market capitalism, the result can be curiously destructive.

Naomi Oreskes explores just one of these examples in Merchants of Doubt, a book about the organized assault of corporate interests on the issue of anthropogenic climate change. The “debate”, she concludes, is not a debate at all. Her research as a science writer found that the scientific community reached supportive consensus for global warming as early as the 1950s. The “strategy of doubt mongering” was initiated by a few powerful industrialists whose economic interests would suffer from any measures taken to reduce carbon dioxide emissions. The empires of profit-making they had built needed to preserve the status quo regardless of the consequences to humanity or the planet. The same obstructionist tactics were employed to suppress concern about the harmful effects of acid rain, DDT, chlorofluorocarbons (ozone depletion), plastics, gasoline additives, food dyes and smoking.

New knowledge that conflicts with an old way of doing things is always difficult to accept. This is the phase we are now entering as we gain new insights into the effects of industrialization on our civilization, our lives and our planet. We are expected to accept, as an act of faith, that mining and polluting, that oil pipelines and tanker traffic, that natural gas and methane wells, that proliferating garbage dumps and stripping the oceans of fish are inevitabilities. They aren’t. Industrialization is our servant, not our master. We invented it so we can change it to suit the wellbeing of ourselves and our life-supporting ecosystems.

We can’t reverse history – we can’t undo what has been done. But we can reshape ourselves, our values, our expectations and our industries. We can make ourselves more aware and responsible, thereby changing what we do and, therefore, our future. Perhaps if we steeled our resolve, thought hard enough and plotted a more promising destination – perhaps if we did less drifting and more steering – we could create prospects for our children and grandchildren that would seem more promising.