In a blog posting yesterday, following a series of major developments at the Cohen Commission, biologist Alexandra Morton suggests she now has enough pieces of the puzzle to pin much of the blame for collapsing Fraser sockeye stocks on salmon farms.

Morton and her team have reviewed over 500,000 documents submitted to the Cohen Commission into disappearing Fraser sockeye over the past year and she would have presented her conclusions to the public sooner, were it not for a confidentiality undertaking she and other Inquiry participants were forced to sign. But as of this week, much of the key evidence upon which Morton is basing her allegations has been officially entered into the record at the Commission and is thus now public.

The final piece fell into place when counsel representing the Clark Government backed down from its opposition to allowing a batch of fish farm disease databases from being entered into the record. The Province’s lawyer had made the argument that concealing information from the public was somehow actually in the public interest. But Monday, following a wave of public protest and negative media, Premier Christy Clark backed down and the records became public.

Morton writes in her blog, “In 1992, the salmon farms were placed on the Fraser sockeye migration route, and the Fraser sockeye went into steep decline…The only sockeye runs that declined were the ones that migrate through water used by salmon farms.” (emphasis added)

For instance, the Harrison sockeye run, which migrates out to sea via the Strait of Juan de Fuca – around the Southern tip of Vancouver Island, thus avoiding all the fish farms – is the one Fraser run that has been experiencing above average returns throughout the past two decades, while all other stocks have plummeted.

As Fraser sockeye nosedived throughout the 1990s and 2000s, DFO apparently became so concerned it asked Dr. Kristi Miller – head of Molecular Genetics at the Department’s Pacific Biological Station in Nanaimo – to investigate. Miller applied revolutionary genomics research to the mystery and came up with some startling findings – the subject of great curiosity of late amongst the media and public, heightened by the Harper Government’s refusal to let her speak publicly about her work.

Miller discovered a “genomic signature” (a sort of genetic fingerprint) in sockeye that were dying in the river before they had a chance to spawn. Upon closer study of the fish and their symptoms, she concluded whatever disease was killing them and leaving its signature was strikingly similar to a virus that was ravaging farmed Chinook salmon in the late 80s and early 90s. This disease was being studied by one Dr. Michael Kent, who appeared as an expert scientist at the Cohen Commission last week just prior to Dr. Miller.

Kent labelled this mystery disease “Plasmycytoid Leukemia” at the time, while the fish farm industry called it “marine anemia”. Recently, Kent has been backing away from his work on the subject, which has complicated things for Miller.

But several key things jump out of this newly public data for Morton – the first being the fact these Chinook farms were located on the narrow Fraser sockeye migratory route through a maze of islands near Campbell River.

Another key issue is timing. In 2008 (the out-migration year for the phenomenal 2010 Fraser sockeye returns), the industry pulled all its Chinook farms along this corridor as it learned of Dr. Miller’s progressing research. Of course, we know those stocks rebounded dramatically. But in 2007, while the disastrous runs that would return in 2009 were swimming past these then-active farms, this mystery disease was peaking.

The Inquiry heard this week that research by the BC Ministry of Agriculture and Lands (the Provincial body with jurisdiction over fish farms at the time), was finding the disease in farmed fish. Morton writes:

What Miller did not know came out today and this is why I think salmon farms are killing the Fraser sockeye.

Four times a year the Province of BC goes out to the salmon farms, picks up approximately five dead farm salmon and does autopsies on them. There are approximately 600,000 farm salmon/farm so this is a very small sample.

While the BCMAL vet apparently does not “believe” in marine anemia, he frequently records the symptoms of this disease in the provincial farm salmon disease database he even notes:

“In Chinook salmon, this lesion is often associated with the clinical diagnosis of “Marine anemia”.

According to Dr. Kent’s studies, this Plasmacytoid Leukemia/marine anemia virus affects farmed Chinook much more so than farmed Atlantics. He did, however, find it can infect wild sockeye.

Morton writes, “Most important to us Kent found it could spread to sockeye. And DFO did nothing. The salmon farms remained on the Fraser sockeye migration route.”

But in addition to this disease, Morton believes another virus, Infectious Salmon Anemia, has also been wearing down Fraser sockeye (unlike marine anemia, farmed Atlantic salmon are highly susceptible to ISAv):

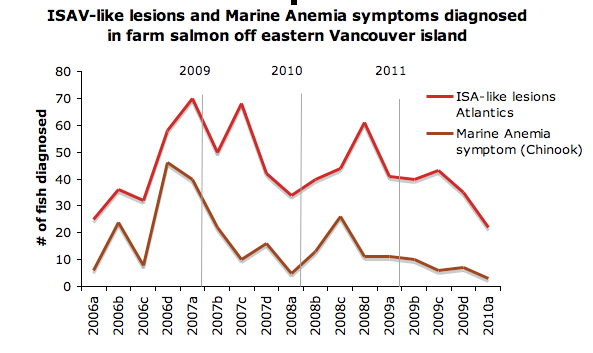

While the province of BC, the salmon farming industry, the Minister of Fisheries, MPs etc., have all been saying infectious salmon anemia is not here the province of BC has recorded the symptoms of this disease over 1,100 times in their database which only a very few people have ever seen. Disturbingly, ISAv symptoms are spiking just after marine anemia symptoms in three different years. Marine anemia is an immune suppressor. This graph looks only data from salmon farms on the Fraser sockeye migration route. The dates 2009, 2010, 2011 refer to the dates those sockeye returns went to sea. For example the sockeye that crashed in 2009, went to sea in the spring of 2007.

The adjacent graph depicts a scary double-barrel viral assault on Fraser sockeye that Morton believes – combined with other stresses in the marine environment that can compound the effects of diseases – is the key to solving the mystery of collapsing Fraser sockeye.

It remains to be seen how Morton’s hypothesis and this flood of new, publicly available data impacts the final months of the Cohen Commission – or public opinion on salmon farms. The Inquiry also learned last week of the lengths Dr. Miller’s own DFO colleagues, the aquaculture lobby, and even the Harper Privy Council Office have gone to to keep Miller from pursuing and publicly discussing her groundbreaking work. Miller even told the Commission – to muffled gasps throughout the court room – that the future funding of her work is in serious question, thanks to policy changes from the Harper Budget Office.

But in light of the seriousness of these allegations and starkness of some of this data now coming to light for the first time, it’s clear that if we have any genuine desire to stem the decline of Fraser sockeye, these diseases need to be taken seriously and studied further with all the necessary resources and departmental and political support they merit.

If the Cohen Commission cannot deliver at least that much, then it will have failed its most basic objective.