The following is the second half of the introduction to Damien Gillis’ multi-part series, “Canada’s Carbon Corridor” – read part 1 here.

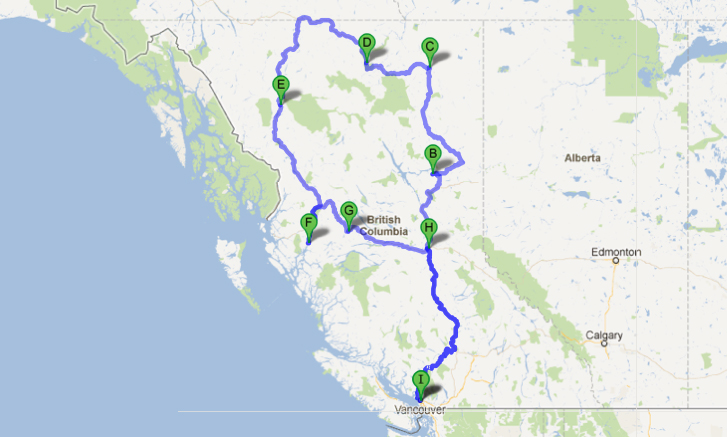

In part 1 of this introduction to what my colleagues and I have termed “Canada’s Carbon Corridor” – an interconnected web of major oil, gas, coal, mining and hydroelectric projects across northern BC and Alberta – I traced the first half of a recent journey by the team producing the documentary Fractured Land, of which I am the co-director. We began our trip amidst proposed coal mines and Site C Dam on the Peace River and through the heart of natural gas “fracking” operations in northeast BC, winding up at Liard Hot Springs.

From there, after passing briefly into the Yukon via the Alaska Highway, we turned south and headed for Tahltan country in northwest BC. There, we spent four days investigating proposed mining projects and more unconventional gas – this time Shell’s plans to develop coal bed methane in the Sacred Headwaters, the birthplace of three vital arteries for the province, the Skeena, Nass and Stikine Rivers.

We spent one day with Wade Davis, National Geogrpahic Explorer-in-Residence and recent author of the book Sacred Headwaters, and the rest of our time with a number of First Nations who have put themselves on the line to block coal bed methane and mines like Imperial Metals’ proposed Red Chris.

This particular project would involve a massive mountaintop removal mine for gold and copper, amid the continent’s largest population of Stone’s Sheep. As such, it has ignited much local opposition. But we also learned that there are many members of the various Tahltan communities who are in favour of this and other mines for the jobs and economic opportunities they promise. This conflict will likely play out for some time to come in these communities, though the tide may be turning against Red Chris for a number of reasons, which I’ll get into in a future chapter of this series.

From the Sacred Headwaters, we travelled south to Kitimat, documenting along the way the construction of the Northwest Transmission Line. This $400 million project is designed to plug BC’s electrical grid into the region in order to power these mining projects – of which Red Chris is but one of many. (Which is why it’s odd that a significant portion of the line’s funding came by way of a federal “green energy” fund!). The transmission line is yet another connection between northwest BC and the proposed Site C Dam in the territory of our central character Caleb Behn – which our provincial government justifies with the contention it is needed to provide power to gas and mining operations.

government justifies with the contention it is needed to provide power to gas and mining operations.

We were all alarmed at the pace of development of the transmission corridor, with upwards of ten different crews working simultaneously to clear sections of the line – carving a 100 or so meter-wide swath through spectacular mountain valleys. Fifty-foot tall teepees of logged trees rim the highway for long stretches, waiting to be burned.

In Kitimat, we met with former Haisla elected chief and recent president of the Coastal First Nations, Gerald Amos, to get a look at the LNG plants proposed and under construction in his territory, along the Douglas Channel. Gerald and his wife graciously took us out on their boat to show us the three main proposed projects – one led by Shell, with partners Korea Gas Corporation, Mitsubishi Corporation and PetroChina Company Limited; another by a consortium of Encana, Apache Canada and Enron Oil and Gas (known as Kitimat LNG); and the third a joint venture in which the Haisla Nation itself is a partner. (It should be noted there are as many as eight LNG plans for Kitimat, but these three would appear to be the most serious and viable).

Only the Kitimat LNG project is under initial construction – clearing the banks of the channel of trees and brush – though its completion has been pushed back by a year, as the consortium has yet to sign any contracts for the product.

Meanwhile, the Haisla just signed a deal with the province to expedite their plant. While his elected leadership is moving quickly forward with its plans to welcome LNG into their territory, Gerald was eager to hear from Caleb about how these decisions will affect his people at the other end of the pipeline. This is some of the much-needed dialogue currently missing around these issues, which we hope our project will continue to foster.

While the Haisla have led the battle against the proposed Enbridge pipeline on their lands and supertankers in their waters, natural gas has proven a different story. Deals signed by the Haisla and the Carrier-Sekani Tribal Council, which provides political and technical support to eight member First Nations in the northern BC interior, appear to have been done with far less communication with other First Nations and the public than that which surrounded Enbridge.

We learned the Carrier-Sekani signed last year a 25-year deal estimated to be worth over $500 million in shared revenue and job training benefits with the proponents of the Pacific Trails Pipeline, which would carry fracked northeast BC gas from a junction point at Summit Lake, north of Prince George, to Kitimat, along virtually the identical right-of-way as the proposed Enbridge Pipeline .

.

On that note, during one of our final stops on the trip, we visited the grassroots resistance camp on the Morice River, southwest of Houston, where members of one clan of the Wetsu’et’en First Nations, the Unist’ot’en, have constructed and are occupying a cabin directly in the path of the proposed Pacific Trails Pipeline. But as they pointed out to us, they’re not opposed to just one pipeline, rather as many as eight different ones, each proposed to pass through essentially the same energy corridor:

- Enbridge’s twin lines – one for diluted bitumen, the other for condensate

- Kinder Morgan’s “Rearguard” bitumen pipeline to Kitimat – introduced last year to shareholders as a backup plan to the controversial Enbridge Northern Gateway line and to Kinder’s own plans to twin its existing Trans Mountain Pipeline to Vancouver (the Unist’ot’en camp is prepared for this line to include a twin condensate line as Enbridge is proposing)

- Pembina Pipelines has a plan – temporarily shelved for “commercial uncertainties” – to run a condensate line from Kitimat to Summit Lake (the Unist’ot’en camp is bracing for this plan to come to the fore again should Enbridge be rejected, and for the possibility it too will include a bitumen line)

- The Pacific Trails gas pipeline (already approved by the province, along with the related LNG plant in Kitimat)

- Shell Canada and its Asian partners’ gas pipeline from northeast BC to their proposed LNG facility in Kitimat (Shell has already selected TransCanada Pipelines to build this line)

Moreover, Spectra Energy recently announced plans to run a gas line to Prince Rupert, north of Kitimat, to connect to their own proposed LNG plant and tankers there.

Is this somehow a conspiracy theory? Hardly. I reported in The Common Sense Canadian over a year ago that Enbridge CEO Pat Daniel has publicly expressed interest in exploiting pipeline “right-of-way synergies”, in building both its twin pipelines and the Pacific Trails gas line together. Enbridge also bought Encana’s controlling stake in the Cabin Gas Plant in Northeast BC last year. And the proposed routes of the above pipelines essentially stack on top of each other for long stretches.

My concern is that while all this attention is being payed to Enbridge, virtually no one – amongst First Nations, the conservation community, or the political opposition (the NDP has publicly supported fracking, the Pacific Trails Pipeline and LNG projects in Kitimat and is at best on the fence about Site C Dam) – is talking about this larger energy corridor, of which Enbridge is merely one small piece.

The Pacific Trails line is approved and the companies are into pre-construction work already. Once the corridor is logged and cleared, it will be far more difficult to stop any one, let alone all of these pipelines and the development to which they connect.

From Site C Dam, powering gas and mining operations, to expanded fracking, which connects to the Alberta Tar Sands through natural gas and condensate, to oil and gas pipelines to our coast and the tankers that would transit our waters carrying these fossil fuels – bitumen, LNG, coal – to new markets in Asia, this is a big deal. The biggest, by far, that this province has ever seen in 150 years of colonial establishment.

It’s time we expand our horizons and broaden our discussion beyond Enbridge – and our team hopes our Fractured Land film project and subsequent columns in this series will act as a catalyst for that much-needed dialogue.

Thanks to Rivers Without Borders for their support with this portion of our recent filming tour for Fractured Land.

Watch for part 3 of the “Canada’s Carbon Corridor” series on this past week’s “Keepers of the Water” conference in Fort Nelson.

deliver a presentation to faculty and students at UNBC, before heading home to Vancouver (an approximately 5,000 km journey, all told).

deliver a presentation to faculty and students at UNBC, before heading home to Vancouver (an approximately 5,000 km journey, all told).  an market with supply, driving down the price for gas, which is why new markets are being sought in Asia, where gas prices are currently much higher.

an market with supply, driving down the price for gas, which is why new markets are being sought in Asia, where gas prices are currently much higher.