The puzzle of British Columbia’s disappearing Fraser River sockeye is unfolding like a classical murder mystery. Suspects abound. Suspicion has fallen on such culprits as atypical ocean predators, unusual algae blooms, overfishing, inadequate food supplies, and threatening high temperatures in both marine and river ecologies. Each suspect has been carefully investigated and each may have inflicted some injury on the hapless sockeye. But the prime suspect is the salmon farming industry, the Norwegian corporations that have located multitudes of open net-pens in BC’s West Coast waters – many crucially situated along the migration routes of the victimized sockeye.

The salmon farming industry possesses the three primary characteristics that make it the prime suspect in this murder investigation: motive, opportunity and means.

The motive is profit. Corporations have discovered that open net-pens are the most lucrative way of rearing farmed salmon. When Norway tightened restrictions on its salmon farming industry because of the proliferation of diseases and parasites in North Atlantic wild salmonids, Norwegian corporations saw their profits being constrained by controls and costs. Their quest for continuing expansion and profit was curtailed.

The perfect opportunity for expansion and profits appeared in coastal BC. The province was eager to boost coastal economies with a new industry, the waters were pristine and cold, regulations were minimal, and supervision was casual, trusting and accommodating. The corporations, of course, promised investment and jobs. This new environment was open, innocent and unburdened by the experience and disasters that had occurred in the North Atlantic. BC was the perfect opportunity to expand the industry and satisfy ever-hungry shareholders.

Corporate character and history are also relevant in this murder mystery. When salmon farming was known to cause environmental problems in North Atlantic waters, when countries such as Norway, Scotland, Ireland and England all had negative experiences with salmon farming, the Norwegian corporations knew that suspicion would likely fall on similar operations in BC. Indeed, parasites and diseases have plagued operations wherever open net-pen salmon farming has been practiced. If corporate practice transferred disastrous viral infections to Chilean waters, then precedent and logic must conclude that these same corporations and operations could bring similar problems to the West Coast. So the corporate defensive strategy has been to separate the events that have occurred elsewhere from those unfolding here.

In a global village interconnected by information sources, however, this strategy is transparently facile and obvious. Numerous independent Norwegian scientists, with long North Atlantic salmon farming experience, have repeatedly warned that the same problems occurring in open net-pen operations there are inevitable in BC. A conspicuous corporate strategy of separating the two situations only arouses suspicion – although evasion suggests guilt, suspicion itself is not incriminating.

Neither is it incriminating that the salmon farming industry always professes its absolute innocence, invariably denying any connection between its practices and any harm to BC’s wild salmon. Its defensive strategy is to argue that no condemning studies are ever conclusive – even though many sea lice studies have repeatedly confirmed harm. Despite the overwhelming weight of incriminating circumstantial evidence, its corporate response is to encourage further investigation – ad nauseam. Repeat definitive studies. Get more data. Quibble about details. Solicit contradictory opinions. “Me thinks,” as Hamlet said of his mother’s guilt, “she doth protest too much.”

No corporation engaged in a harmless practice needs a public relations company to polish an image, especially if that company is Hill and Knowlton, described as one of the world’s slickest “spin machines” ‹ the same one employed by tobacco companies to deny the cancerous effects of smoking, by Exxon to clean its reputation after its disastrous oil spill in Alaska, and by dictatorships to cover the blood and torture of abominable politics. Since the character of a reputable corporation speaks for itself, suspicion is automatically aroused when extreme measures are needed to improve a public image.

The last criteria for identifying a prime suspect is means – did the suspect have the capability of committing the crime? Open net-pens containing millions of salmon in feed-lot conditions undeniably pollute the immediate benthic environment with feces, waste food, antibiotics and the toxins to control sea lice. And the natural sea lice cycle, sustained every year by the migration of wild mature salmon to spawning and death in their nascent rivers, is broken by the continual presence of salmon in farms. The consequent damage to out-migrating wild smolts has been repeatedly demonstrated.

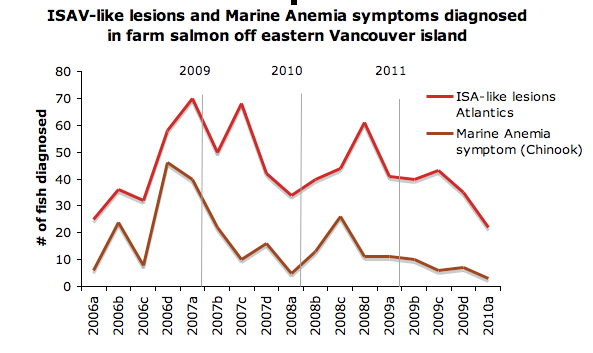

The latest and most serious evidence in the sockeye salmon murder mystery is the possibility that corporations have brought lethal or debilitating viral infections to the West Coast. Symptoms of infectious salmon anemia have been found. And Dr. Kristi Miller, a molecular geneticist who has been studying the decline of Fraser River sockeye – their diminishing returns happen to correspond to the placement of open net-pen salmon farms on their migration routes – has identified genetic markers that strongly suggest another unusual viral infection in wild fish. “It could be the smoking gun,” she testified to the Cohen Commission established to investigate the mystery of the missing sockeye.

Judge Cohen has been receiving mounds of information, including reams of data about parasitic sea lice transferring from farmed to wild fish, and now new evidence suggesting fish farms have imported debilitating viruses to the BC’s West Coast ecology. When his investigation is completed, he will deliberate and report on his findings. The prime suspect has not yet been convicted. But the mounting evidence is incriminating, and various accomplices are now implicated. The plot thickens.