PEI’s Atlantic Veterinary College – cited as the reference lab for Infectious Salmon Anemia – has confirmed that the virus has officially arrived in BC’s West Coast waters. Critics of open net-pen salmon farms have warned that this arrival was inevitable given the history of the disease’s spread from Norway to Scotland, Ireland, Canada’s East Coast and Chile via transported Atlantic salmon eggs used by the industry. Those who are closely attuned to the health of wild salmon and are skeptical of the official monitoring and testing protocols have suspected that ISAv has been here for several years.

The presence of ISAv in wild Pacific salmon is ominous, a threat that casts a foreboding shadow on the entire marine ecology supported by these iconic fish. The disease is highly infectious, prone to mutation and potentially lethal. As an exotic disease previously unknown in the Pacific Northwest, its effect could cause havoc, shaping indefinitely the direction and focus of conservation efforts. The economic, social and ecological costs could be staggering. In short, ISAv’s arrival – almost certainly courtesy of the salmon farming industry – is a potential catastrophe.

As usual, the industry is minimizing the significance of ISAv’s arrival on the West Coast. As a Marine Harvest environmental officer said, “Just because it is present in these Pacific salmon doesn’t mean it’s a health issue…Pacific salmon are not as affected by ISA as Atlantic salmon” (Postmedia News, Oct. 19/11). Indeed. The industry’s gift of ISAv to Canada’s Maritimes is now creating the same problems that salmon farming has caused Europe, probably the near extinction of a population of wild Atlantic salmon in Nova Scotia’s Bay of Fundy. Meanwhile, the industry’s gift to coastal BC is just beginning to be measured.

So, what is the meaning of “Pacific salmon are not as affected by ISA as Atlantic salmon”? The underweight wild smolts identified with ISAv came from BC’s Rivers Inlet, a sockeye rearing area that has declined in five years from Canada’s second largest producer to 1 percent of its historical output – and it’s 100 km from the nearest salmon farm. On the banks of the Fraser River, thousands of unspawned dead sockeye salmon are washing ashore, apparently the victims of damaged livers. Are these some of the “not as affected” effects? In the complex, stressful and unforgiving dynamic of wild salmon surviving a dangerous life at sea and then heroically struggling up their nascent rivers to spawn, “not as affected” can be a lethal handicap.

The 4,726 tissue tests of farmed salmon over eight years, the industry contends, found no evidence of ISAv, although critics say a series of at least 35 reports from provincial government labs have indicated its presence in BC waters – a curious anomaly that is consistent with the self-serving interests that have occupied the industry. Almost without exception, these corporations have shown little more than a token concern for the marine environment that houses their open net-pens. Their public relations strategy has been to minimize their image of environmental damage. Sea lice are natural to marine ecologies, therefore persistent and concentrated infections in open net-pens on the out-migration routes of vulnerable wild salmon smolts are deemed normal. Viral diseases are found in natural ecologies, therefore dense infections that spread billions of viral particles from infected farmed salmon into the surrounding ocean are also normal. Seals and sea lions inevitably die, therefore the wholesale slaughter of them by the thousands is normalized with such a dismissive term as “cull”. If the industry viewed BC as anything other than a place to make money, it would have taken steps years ago to reform its practices and eliminate its environmental impacts.

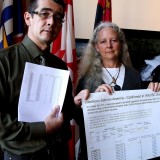

The response of the industry to the newly discovered presence of ISAv in wild West Coast salmon is typical. Says Marine Harvest’s environmental officer – a self serving title that is conspicuously oxymoronic – “As far as we know [Marine Harvest] is clean of this disease and we want to keep it that way” (Ibid.). Of course they do. Given the industry’s $2 billion fiasco with ISAv in Chile, keeping “clean” of the disease is the primary objective. But the real issue of concern is not the business of growing farmed salmon but the health of the entire West Coast marine ecology and its keystone species. Significantly, the initiative to test the Rivers Inlet sockeye didn’t come from the industry or their government supervisors but from Simon Fraser University fisheries statistician Rick Routledge, at the urging of Alexandra Morton.

The next steps of the salmon farming corporations are predictable. They will concede that the information is interesting but that further study is needed. They will argue that identification of the European strain of ISAv found in two of the 48 sockeye smolts from Rivers Inlet could be a mistake or was too small to be meaningful. Or they will argue that the sample was contaminated or misidentified by an unexplainable anomaly. As in the past, their operative strategy will be to deny, delay and obscure.

Because the ISAv was detected in Rivers Inlet’s out-migrating sockeye smolts, this means the virus has likely been in BC waters for at least several years and is now firmly established in the ecosystem. Fish pathology indicates that it may also be in the Fraser River watershed. Indeed, it may now be endemic in BC’s marine ecology. Salmon farming corporations have released this monstrous little genie from its bottle and no amount of effort is likely to capture it.

As for what’s next, brace for a long, slow, tortuous and complicated catastrophe. This uncontrollable contagion could spread southward to California and northward to Alaska via infected herring, wild salmon and other fish species.