[Editor’s Note: This time last year, we brought you in-depth coverage on the ongoing Fraser River gravel mining program and its resulting ecological impacts on salmon and sturgeon spawning grounds – featuring a report by retired DFO senior biologist and manager Otto Langer. One year later, on the eve of another season of mining operations, comes the surprise revelation from DFO that this year’s planned mining of 184,000 cubic metres of gravel from Tranmer Bar, near Agassiz, has been cancelled! The rationale cited was logistical delays and low market

prices for gravel – only confirming critics’ position that this program isn’t safety-driven (for flood risk management, as the public has been told), but rather market-driven. Hopefully this year’s hiatus will provide time for

the public to convince the Province and DFO to permanently scrap

this unnecessary, environmentally destructive program.]

—————————————————————————

We are in the midst of the Cohen Inquiry on the collapse of the 2009 sockeye runs into the Fraser River. Despite that, in the past two years the Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO) continued to approve some of the largest mining programs on Lower Fraser River gravel bars that are essential habitat for salmon, sturgeon and eulachon populations. This is despite the fact white sturgeon and the eulachon are endangered species in the Fraser River and that the Federal government has initiated a 25 million dollar inquiry to determine why its sockeye runs have declined prior to 2010.

DFO and the BC Government signed a five year agreement to mine excessively large quantities of gravel from essential gravel bar habitats in the Chilliwack to Wahleach Creek section of the Fraser beginning in 2004. Considering that the gravel removal agreement ended in 2008, why would gravel mining be an issue in 2011? The agreement ended in 2008 but was extended without any public consultation into 2009, 2010, and now 2011. This lack of public consultation should not be a surprise to anyone in that the original agreement was developed and signed without any attempt to obtain public input.

One can only be critical of government’s way of doing business at the expense of a public resource under the alleged claim of “flood risk reduction”. The Province’s and DFO’s own engineering consultants have concluded in their studies that the large-scale continued long term mining of many essential gravel bar habitat areas will cause long-term hydrological and ecological damage to the river and provide negligible public safety benefits.

A recent inspection of the mining of Gill, Little Big Bar and Hamilton Bars in December 2010 by the Fraser River Gravel Stewardship Committee (FRGSC) showed that the gravel bars had recovered little after the spring freshet of 2010 and two of the bars were mined so as to create ponds that trapped fish and exposed them to dehydration and predation. DFO was specifically warned that the mining practices seen in 2010 would cause that impact, but, again, this public input was not acted on.

A recent inspection of the mining of Gill, Little Big Bar and Hamilton Bars in December 2010 by the Fraser River Gravel Stewardship Committee (FRGSC) showed that the gravel bars had recovered little after the spring freshet of 2010 and two of the bars were mined so as to create ponds that trapped fish and exposed them to dehydration and predation. DFO was specifically warned that the mining practices seen in 2010 would cause that impact, but, again, this public input was not acted on.

Also, the inspection showed that the largest single mining project to date on Spring Bar in 2008 (i.e. 400,000 cubic metres), had recovered little after three freshets and the mining at that site has resulted in a small lake isolated from Fraser River flows. DFO had previously claimed that such sites would rehabilitate in two to three years and therefore habitat compensation works were not required. In addition, temporary bridge structures were left in the river and have posed a great risk to navigation, almost killing two fishermen in one boating mishap.

In the fall of 2010 the FRGSC learned that Emergency Measures BC (EMBC), the promoter of gravel bar mining for alleged flood control purposes, was planning to again mine Powerline and Tranmer Bars in 2011. Despite the costly consultant surveys and impact reviews, the FRGSC was advised that gravel sales were slow and of the two applications submitted, EMBC would probably only proceed on one. This thought process threw doubt on the necessity of gravel mining for flood control purposes. Was this a real flood risk reduction project or a commercial gravel mining venture rationalized as a public safety project? This approach also shows utter contempt for the costs involved and the wild goose chases the public and the reviewing agencies would be led on. Why do costly studies at two sites when one would only be selected at the eleventh hour based on the wrong rationale?

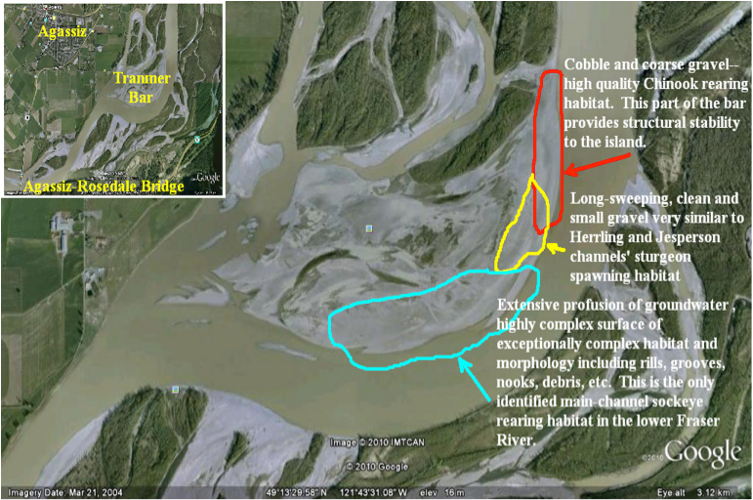

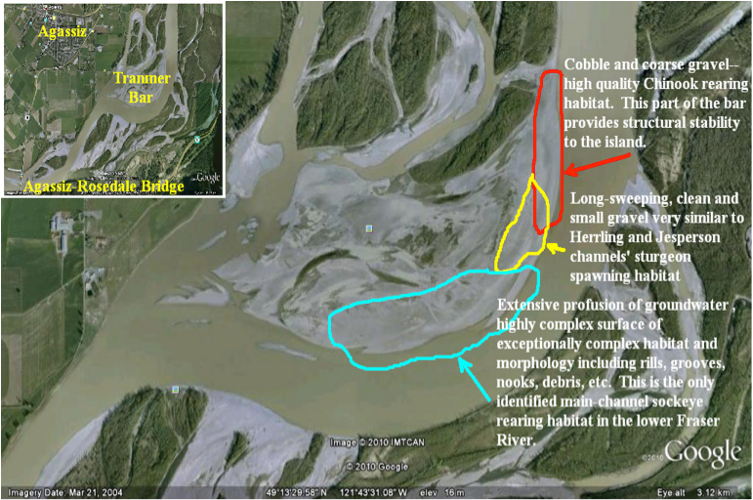

By late December it was obvious that EMBC would only proceed on the mining of Tranmer Bar. Tranmer Bar has been mined repeatedly in the past few years and in 2010 it was dropped from mining plans due to various concerns related to the impacts of mining that site.

To date, the mining of certain bars was allowed by Ministry of the Environment (MOE) and DFO, even though inadequate data existed on the value of those high bar spawning sites to the endangered Fraser River white sturgeon. This despite the fact a DFO habitat engineer previously determined that this bar habitat was in short supply and the value of them has high and the mining activity on them would cause a significant impact.

Sturgeon studies were begun in 2010 but were poorly funded by the Province and initiated in a near-historic low-flow year and were bound to supply very inconclusive results. Despite this, MOE and DFO did not object to allowing more mining in probable sturgeon spawning habitats and the Canadian Wildlife Service of Environment Canada seemed not to care about the use of these habitats by thousands of birds – including swans, blue herons, eagles and many species of ducks.

Studies by the FRGSC in December 2010 showed that the habitat on Tranmer Bar was characterized by many spring-fed streams/backwaters that supported large populations of rearing fish including mountain whitefish and juvenile sockeye salmon and was a resting site for swans. Despite the concerns over the past many years, DFO again determined that public consultation was not necessary in their Fisheries Act and Canadian Environmental Assessment Act reviews. This determination was despite the fact that the public have continuously voiced objections to what was proposed. The proponent (EMBC) has also refused to meet with the public to discuss the program.

Despite this lack of consultation, the DFO CEAA screening report notes that DFO received 18 submissions on the project – most opposed. It was obvious that MOE and DFO largely dismissed public concerns and expedited the approvals in mid-January so the mining could be initiated in order to be done by March 15, 2010. The Province and DFO have an agreement in place to allow an early seasonal review of these projects but in 2011, as in all previous years, they were again some three months behind schedule on their own review and issuing of permits.

The project as approved by DFO allows for the disturbance of 275,000 m2 (68 acres) of Tranmer gravel bar habitat and the mining of up to 184,000 m3 of gravel and the processing of gravel on site for market-ready sales. Considering the very late review and approval of works by the regulatory agencies, by early February the construction of the roads and bridges to allow the mining had yet to begin. The reason given to the public is that EMBC did not have equipment lined up to do the work and the price of gravel is not economic to mine. This is despite the fact that the government in the past has waived the need to collect royalties on such mined gravel.

The above development is rather amazing but not surprising. Several times in the past the BC Government has led the public to fear the next flood and has rationalized the mining of the river’s gravel bars to address the upcoming spring’s flood threats. DFO staff have even convinced their Minister that the mining had to occur or flooding could take place, causing the loss of life and property. DFO then would document in internal correspondence how they were not convinced of the value of the mining as related to flood control benefits and that alternatives such as better dykes could be more effective.

Despite DFO staff reservations, their Vancouver Director General advised them not to discuss alternatives and to not question any EMBC rationale for mining gravel bar habitats. For instance, in 2007 great urgency was put on mining Spring Bar to address floods that could occur that spring due to high snow pack. Despite the Provincial and DFO-created panic, the mining did not take place. When it did take place a year later, DFO consultants and the BC dyke safety engineer noted that the mining would not address any reduction in flood risks and the latter expert said the mining was largely promoted by DFO to allow a local aboriginal band to profit from the sales of gravel so DFO could improve relationships with that band.

To some degree it is obvious that the mining program is being done under a near-fraudulent rationale and the public have been geared up to support the program due to a fear campaign run by certain politicians. The EMBC managers even have admitted that when they took the lead in promoting gravel mining, they said they could best sell it as a flood control program. The MLA for Chilliwack – who has always promoted gravel mining – happened to be the Minister in charge of EMBC at the time and ran his own media campaign to promote gravel mining in the river.

Once again the politics of gravel removal seem not to need a solid and valid scientific rationale. Those who are most entrusted to protect the river and its fish and wildlife habitats have been ordered to not question the need or value of the mining and to learn to deal with the impacts caused by that program. Furthermore, they have not required habitat compensation works so as to assure an ongoing no net loss of habitat as required by the Fisheries Act habitat policy.

One can argue that some gravel removal will always be necessary. Certain bottlenecks to flow will occur. However, such a program must be embedded into an overall long-term environmental management plan for the gravel reach of the Fraser River, similar to the downstream Fraser Estuary Management Plan which was put into place some 30 years ago to address development and environmental protection concerns in that part of the river. Despite the EMBC commitment to annual gravel mining and the ill-advised MOE and DFO support for that program, absolutely nothing has been done by the environmental agencies to require a long-term environmental management plan to protect river values, examine the cumulative long-term impacts of annual gravel mining, develop a convincing flood risk plan, and allow full and open public consultation on this entire issue. Considering that it is now 2011, the absence of this long-overdue basic work and planning is an absolute condemnation of the conservation mandates of the BC Government, DFO and Environment Canada.

One can only draw the conclusion that in the Lower Fraser we can only afford to allow gravel mining for the alleged purposes of flood control when the economy needs and is ready to buy the gravel at an acceptable price. Fortunately, we do not run other public safety programs in the same manner. Imagine if a slide was to occur in the Fraser Valley and the removal of the debris was not addressed until partnerships were in place to mine and sell it!

Our Federal government is committed to a proactive strategy to protect our living legacies for the benefit of all Canadians and, above all, to take a precautionary approach in doing this. Does the use of the Fisheries Act, its supporting no not loss policy, the Canadian Environmental Assessment Act, cumulative impacts and proactive management mean nothing to government over the past decade, especially after years of good progress to better protect the environment in the decades prior to the year 2000? Why should we now step backwards?

Note: On February 16, 2011, I received notice from DFO that EMBC has abandoned the Tranmer Bar gravel mining project for 2011. As previously advised, the cancellation is believed to be due to the very late scheduling of the project by the government agencies, the inability of the Province to line up the equipment to do the job at this late date, and the present low values in the commercial value of the gravel.

Otto E. Langer BSc(Zool) MSc

A recent inspection of the mining of Gill, Little Big Bar and Hamilton Bars in December 2010 by the Fraser River Gravel Stewardship Committee (FRGSC) showed that the gravel bars had recovered little after the spring freshet of 2010 and two of the bars were mined so as to create ponds that trapped fish and exposed them to dehydration and predation. DFO was specifically warned that the mining practices seen in 2010 would cause that impact, but, again, this public input was not acted on.

A recent inspection of the mining of Gill, Little Big Bar and Hamilton Bars in December 2010 by the Fraser River Gravel Stewardship Committee (FRGSC) showed that the gravel bars had recovered little after the spring freshet of 2010 and two of the bars were mined so as to create ponds that trapped fish and exposed them to dehydration and predation. DFO was specifically warned that the mining practices seen in 2010 would cause that impact, but, again, this public input was not acted on.