by Nelle Maxey

It was a beautiful day.

The day was Friday July 26. It was just like any other sunny summer day in the Slocan Valley, located in the West Kootenay region of British Columbia 650 kilometres east of Vancouver.

It was the height of the tourist season. Bed and breakfasts, restaurants, and retail stores were swollen with visitors. Kayaks, canoes, rafts and tubes filled the Slocan River as swimmers cooled themselves at public and private beaches along the river. Others were in their gardens, assessing if the beans were ready for canning and the garlic ready for digging. People picked raspberries and blueberries from the loaded bushes, dug potatoes, plucked zucchini, and lettuce for dinner. It was a bumper year for gardens in the valley. Farmers were in their fields cutting hay. Market gardeners and local greenhouses irrigated their crops and picked produce to sell.

All this of course was normal. What wasn’t normal, however, was the drone of helicopters flying over the Slocan Valley’s Winlaw area, dumping water scooped from the river on the two-day old Perry Ridge fire.

Then disaster struck the Slocan Valley.

At about 1:30 p.m., a large tanker truck delivering jet fuel for the Ministry of Forests fire-fighting helicopters tumbled into Lemon Creek and dumped 33,000 litres of jet fuel into the swift-flowing creek which joins the Slocan River downstream of the spill.

The driver was on the wrong road. If the driver was on the right road, they would have used Uris Road north of the Lemon Creek bridge. The tanker was on Lemon Creek Road south of the bridge. This stretch of road is a narrow, decommissioned logging road that had been closed to traffic due to slides and crumbling banks.

In the official record of what happen, one report says the driver was to meet forestry personnel who would direct them to the helicopter staging area. This never happened. Instead, the driver proceeded on his own up Lemon Creek Road, past two signs that indicated the road was closed. The driver eventually found a place to turn around and was on his way back down to Highway 6 when a road bank gave way under the weight of the tanker.

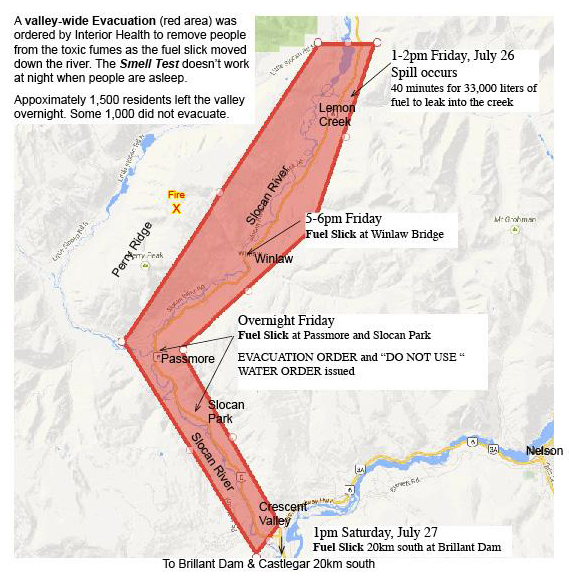

The driver, not seriously injured after the accident, scrambled up the 15-foot bank and walked the 6 kilometres back to Highway 6 where a passing vehicle picked him up so he could report the accident. RCMP arrived on the scene at approximately 3:30 p.m. in the afternoon, although the fumes were so bad they could not approach the area. Once it was confirmed the truck was carrying jet fuel, the Interior Health Authority was notified at 6 p.m. on Friday evening. A few hours later, the first evacuation order was issued for 800 residents within 300 meters of Lemon Creek and the Slocan River for 3 kilometres upstream and downstream of the spill. It took many hours before the volunteer firemen and search and rescue teams could be organized to notify residents of the evacuation order. The first phone calls went out around midnight with volunteers going door-to-door in the most affected areas.

Meanwhile back at the spill site, officials estimate the tanker released the 33,000 litres of fuel in about 40 minutes. The fuel slick reached the Winlaw Bridge sometime around 6 p.m. (about the same time the local health authority was notified of the accident). Children swimming in the river near Appledale just north of Winlaw were later reported to have skin rashes. People who were canoeing in the area also reported health effects. Residents along the river between Winlaw and Lemon Creek reported that the smell was so strong by 5 p.m. that they closed up their homes and left the area. Within 24 hours of the accident the slick had traveled 60 kilometres: down the Slocan River, then into the Kootenay River to just above of the Brilliant Hydroelectric Dam at Castlegar. The first boom to stop the slick was established there on Saturday afternoon.

The plume was 2 to 3 kilometres long and 30 to 50 metres wide. A Ministry of Environment spokesperson said a boom was put in place at about 1:30 p.m. on Saturday just above the Brilliant Dam. The spokesperson said the boom’s effectiveness in containing the fuel was being monitored. Officials didn’t know at this time if fuel had entered the dam works.

The evacuation

Within hours of the first evacuation notice issued by the Interior Health Authority, the evacuation was expanded to include everyone in the valley. Anyone living within a 3 kilometre radius of the river between Lemon Creek and Playmore Junction (where Hwy 6 joins Hwy 3 to Nelson and Castlegar) were to evacuate. This affected 2,500 residences. As the fuel progressed down the river, health authorities had become worried sleeping people would not smell the fuel.

People with emergency services and volunteer fire departments began making phone calls and knocking on doors. The evacuation order included a “Do Not Use Water” order to “all users of water supplies within 10 kilometers downstream of the spill.” Later, the wording of the order changed to suggest water wells were okay to use. This was revised again to say shallow wells near the river might be affected. Today, a week after the accident the order explains that if your creek surface water or well water doesn’t smell like jet fuel, then it’s okay to use. Essentially, a smell test was the only test for private water supplies that didn’t originate from the rivers or Lemon Creek. The evacuation order also contained the following statement: “Jet fuel poses an immediate health risk to people. Exposure can burn skin, inhalation can harm respiratory systems and may cause brain damage. It is also dangerous to consume.”

The boundaries of the evacuation and a timeline of events are shown below:

Fifty volunteer fire fighters from the four valley fire departments worked overnight and into Saturday to notify residents of the evacuation. Even though they had help, they concentrated on people closest to the river and spill site. They notified over 800 residents in all. Much of the notification went by word of mouth to neighbours, family and friends, all of which took place at night. Many residents in the north end of the valley left even before the order was issued due to the heavy concentration of fumes.

By noon on Saturday, the fumes had dissipated enough to lift the evacuation order. Residents trickled back into the valley all day Saturday. Unfortunately, at the north end of the valley some people returned to homes that were saturated with the smell of fuel. Even people’s gardens and hay fields were contaminated, not to mention the watering tanks for livestock had a layer of fuel on top of the water.

By this time, people in the valley settled down and most residents assumed the scare was over. Then the town hall meeting was held.

Many questions, few answers

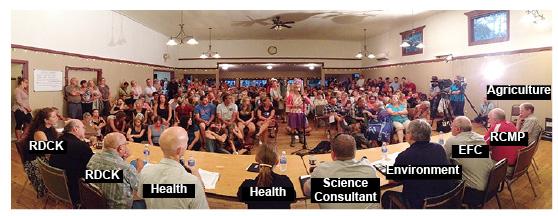

On July 30, hundreds of residents from all areas of the valley jammed Winlaw Hall for a meeting to hear presentations from local government officials, provincial authorities and employees from the company involved. The meeting was not well organized. The handouts did not contain contact information or the names of the speakers. At first, many residents did not have their questions answered as they were told they were not on topic. Then the format was changed and residents were allowed to ask questions of any panellist. Many questions required responses from multiple panellists.

The health official immediately declared the serious nature of this event and explained the reasons for the evacuation. Though benzene was not a component of the jet fuel spilled in the creek, kerosene was a component and is dangerous by skin contact or ingestion. This applies to humans and animals. Aquatic life is at special risk as the specific type of fuel spilled (Jet Fuel A1) is listed to have a chronic toxic effect on aquatic ecosystems.

Residents were informed the “Do Not Use Water” order would stay in effect for 5 to 10 days at a minimum. The order applied to recreation in the river as well as water use from the river and Lemon Creek. All such water systems should be shut down so the contaminated water is not drawn into pipes and hot water heaters. Other surface water users from the creeks not affected directly should use their own judgement and apply the “smell test” to their water. Deep wells were unlikely to be affected. Shallow wells along the river should not be used as they may be contaminated.

This was the first time some residents heard the information about shallow wells and surface creeks. Individual water licence holders or well owners would not receive assistance to have their water tested. Registered purveyors on water systems with more than two users could receive assistance to have water testing done. Residents were also told to wash all vegetables 3 times for 3 minutes before use with potable water (a Catch-22 for residents without potable water supplies), and were also told not to buy local produce.

As residents poured into the line-up for the mic and began asking questions and sharing their stories, the consequences of the spill and the fact that little help had been available were becoming more apparent. The problems associated with the spill were most severe at the north end of the valley, from Lemon Creek to Winlaw. Homes were contaminated with the fuel smell. Fruit trees and vegetables were contaminated. Hay fields and pastures were contaminated. No water was available for livestock, poultry or gardens.

Many people were without any water for drinking, washing dishes, flushing toilets or showering. Similar water problems prevailed all along the river to the lower valley – especially contaminated hay and pastures, no water for gardens and livestock, as well as difficulty hauling enough water from potable water tank stations for resident needs. The meeting was held five days after the spill and potable water tanks had been set up in four locations in the valley only on the day of the meeting.

As of Saturday, August 3, the water and the rocks in Lemon Creek still smelled of jet fuel. There was a sheen visible and emulsion (milky-looking jet fuel and water mix) under rocks in the creek at the Lemon Creek bridge on Highway 6. The road has been remediated just before the accident site where fuel spilled from the tanker. There is no fuel on the road at the actual location where the truck went off. There is water from seeps in the rock face running across the road at that location. You can see this water in published photographs. Workers at the site agreed that the water run-off contributed to weakening the bank that collapsed under the truc, resulting in the fuel spill.

Recent developments:

- Until further notice, a “Do Not Use” order for drinking water and recreational use remains in effect for Lemon Creek, Slocan River and Kootenay River above and below Brilliant Dam. Fuel is still visible in the containment booms and along the shoreline.

- Garden vegetables, fruit, eggs, and dairy milk that were contacted by the fuel vapor are SAFE to consume as long as they do not smell like fuel or have a fuel sheen. Interior Health is advising residents to thoroughly wash fruit and vegetables with alternate water sources to remove any dirt and debris prior to consumption. Food products that have been irrigated with contaminated water AND smell like fuel should be discarded.

- Aproximately 1,000 litres of contaminated material has been recovered.

- RCMP have issued Vessel Operating Restrictions for the Slocan River from Lemon Creek to the Kootenay River, which will be lifted when the clean-up has been completed.

- The smell of jet fuel is still apparent in the Lemon Creek area and responders equipped with gas monitors have been testing the air quality outside residences close to the spill site.

- Many residents in the valley are still waiting for promised testing.

- A Resiliency Centre is being established at the Winlaw Elementary School to support residents with shower, lavatory and emergency support services. It is expected to open within the next couple of days.

- Polaris Applied Sciences from Kirkland, Washington was hired to conduct a Shoreline Clean-up and Assessment Technique, or SCAT. Leading the SCAT team is Polaris principal, Dr. Elliott Taylor, a world-renowned expert in spill clean-up operations. The assessment is underway and is already providing additional information which is helping to clean up the waterways by providing operational focus to the response teams and prioritizing where we focus our attention.

- Light “flushing” activities are being conducted to free product (Jet Fuel A1 / without additives) from stream banks and vegetation to make it available for collection. Nearly 1,000 metres of containment boom has been deployed throughout the Slocan River system and it is capturing any free-flowing product. The product is being skimmed off the water into a vacuum truck and removed to a licensed waste facility. In areas where soil is impacted, the soil is being removed and trucked to a separate licensed waste facility. A significant amount of contaminated water and soil was recovered.

- Experts continue to collect water samples, sediment samples, and fish and wildlife from the impacted water courses. Wildlife mortalities to date have been collected and sent to the laboratory for analysis.

- Water quality test results are being sent to the Interior Health Authority to assist in making a decision on when the “Do Not Use Water” order may be lifted.

- Responders equipped with gas monitors have been testing the air quality throughout the area of potential and observed influence. To date, atmospheric concentrations have been within established government standards; however, the smell of jet fuel is still occasionally apparent.

Nelle Maxey is a grandmother who lives in the beautiful Slocan Valley in south-eastern BC. She believes it is her obligation as a citizen to concern herself with the policies and politics of government at the federal, provincial and local level.