What makes a city great? Among other things, great cities are tolerant communities that welcome and celebrate ethnic diversity. They support and foster local arts, have access to venture capital to spur entrepreneurship and innovation, and benefit from healthy local environments with clean air, clean water and access to nutritious, locally grown food.

New York City is world class, not just because it’s a driver of global finance and a hotbed of cultural innovation; it’s also known for its green spaces, like Central Park and the award-winning High Line.

San Francisco is celebrated for its narrow streets, compact lots and historic buildings. These contribute to the city’s old-world charm, but they’re also the building blocks of a more sustainable urban form. They facilitate densification and decrease the cost of energy and transportation for businesses while improving walkability.

When it comes to urban sustainability, cities in the U.S. and Canada are employing innovative programs and policies to improve the health and well-being of residents and their local environments, like reducing waste and improving recycling (Los Angeles), containing urban sprawl (Portland), conserving water (Calgary) and passing policies to combat climate change (Toronto).

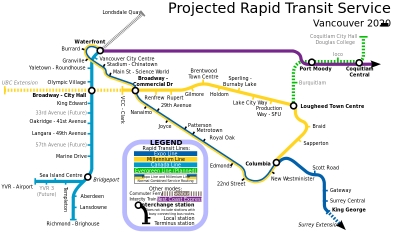

But most cities in Canada and the U.S. are lacking in infrastructure to move millions of people safely and affordably. With some notable exceptions, such as Vancouver and Calgary, no successful rapid transit infrastructure projects have been built in Canadian cities for decades.

A recent survey of urban experts and other “city-builders” across Canada – planners, municipal politicians, academics, non-governmental organizations, developers and architects – concluded the abysmal state of public transit is the Achilles’ heel of urban sustainability and is holding many cities back from achieving greatness.

Toronto residents spend more time battling congestion to get to and from work than in any other city in North America. This shouldn’t be a surprise, as successive governments have failed to sustain and expand transit systems, even though the region has grown by about a 100,000 new residents a year. Toronto now scores 15th of 21 on per capita investment in public transit among large global cities – well behind sixth-placed New York City, which spends twice as much.

This failure to address transit infrastructure is serious. The Toronto Board of Trade estimates congestion costs the economy $6 billion a year in lost productivity.

Furthermore, air pollution from traffic congestion is a major threat to public health, especially for our most vulnerable citizens, like children and the elderly. According to the Toronto Board of Health, pollution-related ailments result in 440 premature deaths, 1,700 hospitalizations, 1,200 acute bronchitis episodes and about 68,000 asthma-symptom days a year.

Fortunately, politicians are starting to respond. Ontario’s government plans to spend billions to expand its regional transit system in the Greater Toronto and Hamilton Area, under a plan called the Big Move. It’s also looking at new financing tools to ensure funding levels are adequate and continue into the future. But before we spend enormous amounts on improvements, we need to ensure projects contribute to a region-wide rapid transit network using the latest technology and adhering to the highest sustainability standards. They should also move the most people in the most cost-effective way.

That’s why a proposal to use diesel trains for the Air-Rail-Link plan to connect downtown Toronto with its international airport in Mississauga is concerning. A rapid transit link with the airport is long overdue, but heavy diesel trains emit particulates and other contaminants, including known carcinogens. The proposed rail line would be close to dozens of schools and daycare centres, several long-term care facilities and a chronic respiratory care hospital.

Numerous experts, including Toronto’s Medical Health Officer, have urged the Ontario government to abandon its diesel plan in favour of electric trains that could be better integrated into a region-wide rapid transit network.

Vancouver, San Francisco, Portland, Seattle and New York City have consistently ranked among the most livable cities on the continent, in part because they take the environment into account for planning decisions. They all have world-class public transit systems that move residents in a safe, affordable and sustainable way. It’s time for Toronto and its suburbs to do the same. Effective transit and transportation solutions can spur economic productivity, protect the environment and improve quality of life.

Written with contributions from David Suzuki Foundation Ontario and Northern Canada Director General Faisal Moola.

Sunday, 09 June 2013 10:22 posted by John King

Zwei:

Bellicose: Demonstrating aggression and willingness to fight.

I can’t say Suzuki’s article is aggressive in any way. The links provide proof to his argument, which is really quite a simple one. Create transit systems to improve overall human health, as well as the environment’s health. There’s really no political agenda behind the words, just a simple aim to help animals, and the environment that sustains them.

It’s really quite difficult to subvert this position no matter how hard one may try.

Thursday, 06 June 2013 15:34 posted by Zwei

@ John King

Sorry old chap, but Suzy didn’t use any facts, just bellicose rhetoric.

Who has copied Vancouver by using Skytrain? No one, in fact Vancouver , if anyone cares, is a poster boy/girl for not how to build your transit.

All politicians are doing in Canada is spending massive amounts of money on grossly gold-plated transit schemes that will do little to alleviate transit chaos, but will enrich friends of the government. When a new SkyTrain line is built, the cement companies have a fiscal orgasm over the massive profits from cement sales.

Thursday, 06 June 2013 11:07 posted by John King

zweisystem:

I think our readers here at the Canadian understand what the word Lysenkoism means, and if there are a few who don’t, they are able to Google it themselves.

You present some arguments but do not support any of your opinions with facts as David Suzuki does with the links provided.

I was raised in Vancouver. I remember taking transit more than a decade ago. Transit in Vancouver today is much more “convenient” than it was then.

Thursday, 06 June 2013 08:06 posted by zweisystem

Really, Susy just doesn’t get it. Oh yes, we have the “rapid transit is good for you” hype, but the article is woefully short on fact and smacks of Lysenkoism.

Lysenkoism: describes the manipulation or distortion of the scientific process as a way to reach a predetermined conclusion as dictated by an ideological bias, often related to social or political objectives.

Throwing more money at TransLink and expanding our SkyTrain mini-metro will not solve a thing.

The Canada Line, despite the continued hype by the mainstream media, has failed to attract ridership in sufficient numbers to justify the expense. Too expensive to extend and too much political and bureaucratic prestige has been spend on this metro, the CL will linger into obscurity.

This unfinished portion of the Millennium Line, the Evergreen line is more of the same, over built for what good it will do.

What attracts people to transit is convenience and our transit is greatly inconvenient and the stats from metro Vancouver support this – The modal share of people using cars has remained at 57% from 1994, when there was only one mini-metro line and 2011, when there was three mini-metro lines.

Thursday, 06 June 2013 04:06 posted by Lloyd Vivola

Efficient, clean and, in some cases, expanded public transport is vital to the general health of cities and for maintaining good air quality. But with all due respect, the model and reasoning intrinsic to this article may leave much to be desired if we do not recognize the impact mass transportation has had on modern urban culture and development. The extensive transit systems of New York and San Francisco have not insured a decrease of vehicular traffic. They have also facilitated the sort of sprawl that further compromises marine and riparian ecology. Also food security. Staten Island in NYC had working farms 50 years ago: Long Island a formidable farming industry. Today farmers truck longer hauls to supply trendy farmer markets which serve only a small part of the population. Golden Gate and Central Parks are gems, but increasingly serve elites and tourists. Parks are vital, but like crunching numbers regarding density and carbon footprints, they do not alone cultivate deeper ecological awareness and behavior. Thus we need to rethink future urban and rural planning holistically, relatively, and also for the sake of better preserving wilderness and conserving natural resources.