Dr. Mark Jaccard, professor of economics at Simon Fraser University and a winner of the Nobel Peace Prize for his contributions to the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, was arrested on railway tracks near Vancouver for blocking the arrival of a Burlington Northern train loaded with Wyoming coal bound for nearby Deltaport and then Asia. Before being released from police custody, he was fined $115 for his May 5th, 2012, trespass violation under the Railway Safety Act, as were the other 12 people in his protest group. “Putting myself in a situation where I may be accused of civil disobedience is not something I have ever done before,” said Dr. Jaccard (CBC, May 5/12). He now joins at least another of his august colleagues, Dr. James Hansen, in this distinction.

Dr. Hansen is one of the world’s foremost authorities on global warming, internationally recognized and awarded for his studies, insights and conclusions on the disruptive effects of greenhouse gases on climate and ecologies. He has been arrested in 2009, 2010 and 2011 for similar protests. During testimony given before the Iowa Utilities Board in 2007, Hansen likened coal trains to “death trains”, contending that they would be “no less gruesome than if they were boxcars headed to crematoria, loaded with uncountable irreplaceable species.” In his assessment, carbon dioxide emissions from burning fossil fuels must be curtailed or the environmental consequences will be catastrophic.

Dr. Jaccard echoed this warning with his own eloquence. “The window of opportunity for avoiding a high risk of runaway, irreversible climate change is closing quickly,” he said. “Within this decade we will either have steered away from disaster, or have locked ourselves onto a dangerous course. Our governments continue to ignore the warnings of scientists and push forward with policies that will accelerate the burning of fossil fuels. Private interests — coal, rail, oil, pipeline companies and the rest — continue to push their profit-driven agenda, heedless of the impact on the rest of us.” Meanwhile, he adds, government response to climate change concerns are “entirely inadequate” (Ibid.).

As a concerned grandfather, Dr. Hansen worries about future generations. So does Dr. Jaccard. “I now ask myself how our children, when they look back decades from now, will have expected us to have acted today,” he said. “When I think about that, I conclude that every sensible and sincere person who cares about this planet and can see through lies and delusion motivated by money, should be doing what I and others are now prepared to do.”

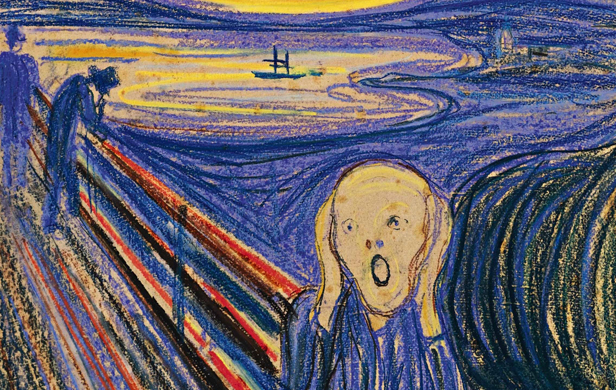

These two scholarly, prominent and respected scientists have been radicalized by the shrinking distance between uncontrollable climate change and our options for preventative action. They are not alone in their recognition of the tragic loss of opportunity as government and industry habitually fail to implement the strategies known to reduce CO2 emissions. The level of frustration, exasperation and desperation in scientists everywhere is intensifying as they gauge the seriousness of our situation against a history of empty promises.

This history is nicely summarized in a documentary, Earth Days (2010) by the American cinematographer, Robert Stone. His film captures the evolution of a crisis as it unfolds during the last half-century. It begins with grainy images of US President John F. Kennedy promising that natural places will be saved for Americans to appreciate in a distant 2000, “If we do what is right now, in 1963.”

Subsequent US presidents discover that merely protecting natural places won’t be enough. Kennedy’s successor, Lyndon B. Johnson warns, “Either we stop poisoning our air or we become a nation in gas masks, groping our way through these dying cities, a wilderness of ghost towns that the people have evacuated.” Then Richard M. Nixon cautions, “The great question of the ’70s is, shall we surrender to our surroundings or will we make peace with nature, and begin to make reparations for the damage we have done to our air, to our land and to our water.”

When the “energy crisis” of the ’70s hits, a worried President Gerald Ford promises to “…accelerate technology to capture energy from the sun and the earth for this and future generations.” The next US president, Jimmy Carter, is alarmed enough to advise, “If we fail to act soon, we will face an economic, social and political crisis that will threaten our free institutions.”

Then Ronald Reagan pledges, “We must and we will be sensitive to the delicate balance of our ecosystems, the preservation of endangered species, and the protection of our wilderness lands.”

As for the intended environmental measures of George H.W. Bush, he is equally reassuring. “It is said,” he notes, “that we don’t inherit the Earth from our ancestors but that we borrow it from our children. And when our children look back on this time and this place, they will be grateful.”

Bill Clinton, with ever-clearer scientific evidence, warns, “If we fail to reduce emissions of greenhouse gases, deadly heatwaves and droughts will become more frequent, coastal areas will flood and economies will be disrupted. That is going to happen unless we act.”

Finally, George W. Bush observes obliquely but succinctly, “And we have a serious problem. America is addicted to oil.”

In the 49 years since 1963, as environmental awareness has grown, some measures have been implemented to protect ecologies and reduce industrial pollution. But greenhouse gas emissions, a key issue, have continued to rise rather than fall. The United States has abandoned the Kyoto Protocol legal efforts to reduce these emissions. Canada’s endorsement of the Protocol was entirely hollow, and it has since given notice of its withdrawal. The current Canadian government assiduously avoids any mention of climate change and is even cutting relevant scientific funding — not encouraging for an expectant public and hopeful scientists.

As Dr. Jaccard was being led away in handcuffs from the stalled Burlington Northern coal train, he was asked by a reporter, “Was it worth it?” And he replied, “I don’t know. We’ll know — our kids will know — in two decades.”