Since international agreements have been unable to reduce our carbon dioxide emissions — 20 years of negotiations and effort have resulted in emissions going up rather than down — those concerned about global warming had hoped that the anticipated decline in petroleum supplies would force a solution. If the availability of accessible oil and natural gas were to dwindle, nations everywhere would be compelled to find energy sources that were less carbon intensive. But fracking has put an end to that hope.

The relatively new technique of “hydraulic fracturing”, a process of drilling horizontally in shale beds and then breaking the rock by injecting a concoction of water, sand and toxic chemicals under extreme pressure, is releasing huge quantities of oil and natural gas. In addition to polluting a subterranean frontier, the global result is a total reconfiguration of the energy equation.

The economic effects are the most obvious. Natural gas is flooding the energy markets in North America and Europe, and is likely to do so elsewhere. Fracking is releasing massive amounts of natural gas in the US, reducing the price below production costs and undermining the market value of Canadian exports of gas. The economic result for BC and Alberta is a collapse of royalties to governments. And low natural gas prices may threaten the economic viability of gas lines and LNG plants planned for BC’s West Coast.

The same economic dynamic is occurring with oil. The International Energy Agency (IEA) estimates that the success of fracking could make an oil-starved America into the world’s largest producer by 2020, and a net exporter by 2030. This reduced dependence on foreign oil questions the Canadian government’s wisdom of relying on the export of petroleum resources as the country’s principal economic plan. It also casts doubt on the viability of the energy-intensive methods used to extract oil from the tar sands.

These new supplies of domestic oil in the US and other countries are likely to change global geopolitics. Saudi Arabia, for example, may lose its privileged position in the global energy equation, and thereby lose the Western support that has been key to its political security. China and India might make moves to replace the West as the strategic friend of existing oil producers. Meanwhile, generous oil supplies will reduce its market price, thereby encouraging world economic activity and further eroding the only effective incentive that has reduced oil consumption, cut carbon dioxide emissions and slowed global climate change.

So the fracking that has become the solution to shortages of gas and oil now presents a host of problems that will ultimately be far more serious than the challenge of slowly weaning our modern civilization from petroleum. “The climate goal of limiting warming to 2°C is becoming more difficult and more costly with each year that passes,” notes the IEA.

The reality is that we are running out of manoeuvring room. “Four-fifths of all carbon emissions that are supposed to be allowed by 2035 to keep warming below two degrees Celsius are already locked into power plants, factories and buildings,” writes Jeffrey Simpson in the Globe and Mail (Nov. 21/12). “If strong action is not taken by 2017, all the emissions necessary to keep warming below that level will be locked in,” he adds. Global consumption of oil, thanks to fracking, is expected to rise a third by 2035, driving “the long-term average global temperature increase to 3.6 degrees Celsius” (Ibid.).

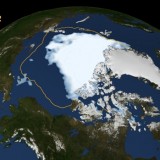

We are already feeling the impact of global temperature increases of 0.8°C. An increase of over four-times this amount would have environmental consequences that we can scarcely imagine. George Monbiot, writing in the Guardian Weekly (Oct 26/12) provides a hint. “A paper this year by the world’s leading climate scientist, James Hansen, shows that the frequency of extremely hot events…has risen by a factor of about 50 in comparison with the decades before 1980. Forty years ago, extreme summer heat typically affected between 0.1% and 0.2% of the globe. Today it scorches some 10%.”

Ocean levels are already rising, causing coastal US cities such as Norfolk, Virginia, to flood regularly from heavy rainfall and small storm surges. Although the disasters that recently befell New Orleans and New York cannot be attributed specifically to global climate change, weather modelling suggests that such events will likely become so commonplace that smashed and flooded coastal cities will appear in lists rather than individually. Severe droughts and storms would become almost too routine to be news. All but the most extreme of the extreme weather events would just be dismissed with generalizations such as “just another bad day on Earth”.

Climatology tells us that during the last 10,000 years we have been living in one of the most benign, stable and accommodating periods in all of human history. Our global civilization is founded upon this predictable comfort. Our cities crowd shorelines because these locations have been safe and convenient. Our food production is based on mild and rhythmical weather. Our renewable resources depend upon a regular climate for regeneration. We alter this normalcy at our peril.

The carbon dioxide we are adding to the atmosphere is now occurring at a rate six times faster than the most rapid natural emissions of any geological epoch of which we know — we are doing in 500 years what nature once did in 3,000 years. This single, traumatic past event caused one of the planet’s most disastrous biological extinctions. Put simply, a future created by excessive carbon dioxide emissions is not going to be comfortable or promising.

Our ingenuity is not an asset if it is used to solve the wrong problems. Indeed, if the biggest threat now confronting us is caused by burning petroleum as our principal energy source, then the more we do to find and use this fuel, the worse our problem becomes. In a future review of our history, we will likely conclude that fracking created a bigger mess than it solved.